“Every myth expresses, in a form narrated for a particular case, an eternal idea, which will be intuitively recognised by he who reexperiences the content of the myth.” - Hans Leisegang, Die Gnosis, Leipzig, 1924, p. 51

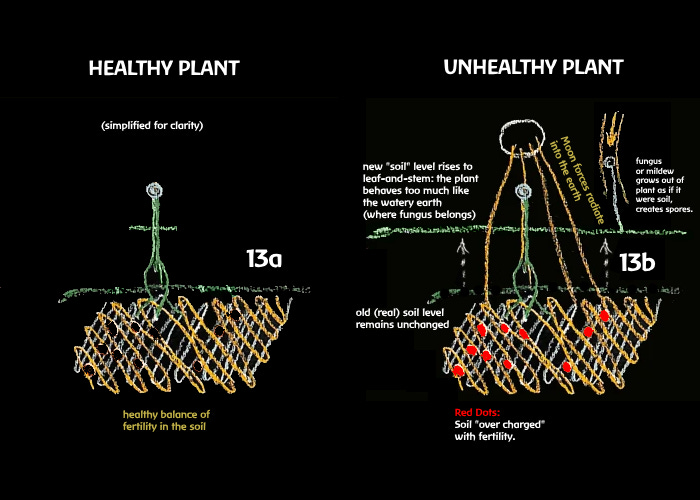

Many of you have experienced blossom end rot in your tomatoes or squash. Others will have experienced powdery mildew on the leaves of your plants. An orchardist likely has experienced fire blight. All of these, in biodynamics, are seen as originating from a similar source: an excess of a particular kind of food (or “forces”). Every pathogenic process is an otherwise healthy process in the wrong place. So what is in the wrong place? In fungal diseases, we find a situation where the plant is too soft — instead of being more mineralized with a tough skin, it is too soft and too much like the watery earth. Steiner describes this as resulting in “decaying life form[ing] another level above the soil level.”1 Put simply, too many byproducts of active decay make the plant above ground a suitable substrate for fungus, which should normally find this form of nourishment below the soil and not in plants. The “soil level” moves up to the leaves.

In his aphoristic2 lectures on biodynamics, Steiner speaks of excessive “moon forces,” which may seem like a rather cumbersome way to describe something quite concrete. It is important to remember that Steiner himself calls what he shared in the Agriculture Course “aphoristic” sayings as a kind of shorthand spiritual-science. Steiner doesn’t say “moon forces” to be cryptic, but to condense what would really take the entire universe to explain fully. As such, what Steiner shared in these particular lectures is necessarily incomplete. What Steiner gave us is closer to a book of agricultural proverbs than the whole picture. After all, he had expected all in attendance — who were not primarily farmers — to be fully familiar with his Theosophy and Outline of Esoteric Science. To jump in blind to the Agriculture Course without familiarity with Steiner’s earlier monographs is like trying to study the Book of Revelation with no familiarity with the Torah or the Talmud or first temple mysticism. If we wish for biodynamics to move forward, we must be willing to go back to its wellsprings.

When fertilizers are excessive — or one-sided, which is another form of excess — plants suffer various “rust” ailments like fire blight, corn smut, blossom end rot, etc. These can be produced from excessive “greasy” organic matter in the soil - old, slimy, anaerobic organic matter, you might say. We always strive for new organic matter in biodynamics, maintaining a constantly adapting balance between consumption and replenishment, decay and buildup.

The plant may become stunted because of its overwhelming attachment to Mother Earth. “It is through a too strong working of the moon that forces working upward from the earth are prevented from reaching their proper height. The powers of fertilisation and fructification depend entirely upon a normal amount of lunar influence. It is a curious fact that abnormal developments should be caused not by a weakening but by an increase of lunar forces.”3 Myths are much more holistic — and memorable — than abstract ideas about “forces” because forces can never be studied except in concrete instances of living plants. We can speculate all we want from an armchair, but we can only learn the facts in the field. Many myths would serve us here, and one is the story of Attis.

Equisetum and Fungus: Good and Bad

In a prehistoric epoch, the earth was too hot for water to condense into rivers, lakes, or oceans. Instead, other compounds like silicon were fluid. We might say molten but the entire earth did not yet have a solid crust. The earth was once too hot for water to condense into rivers, lakes, or oceans. As Steiner says, “As long as the earth was soft, such forces were still in it.”

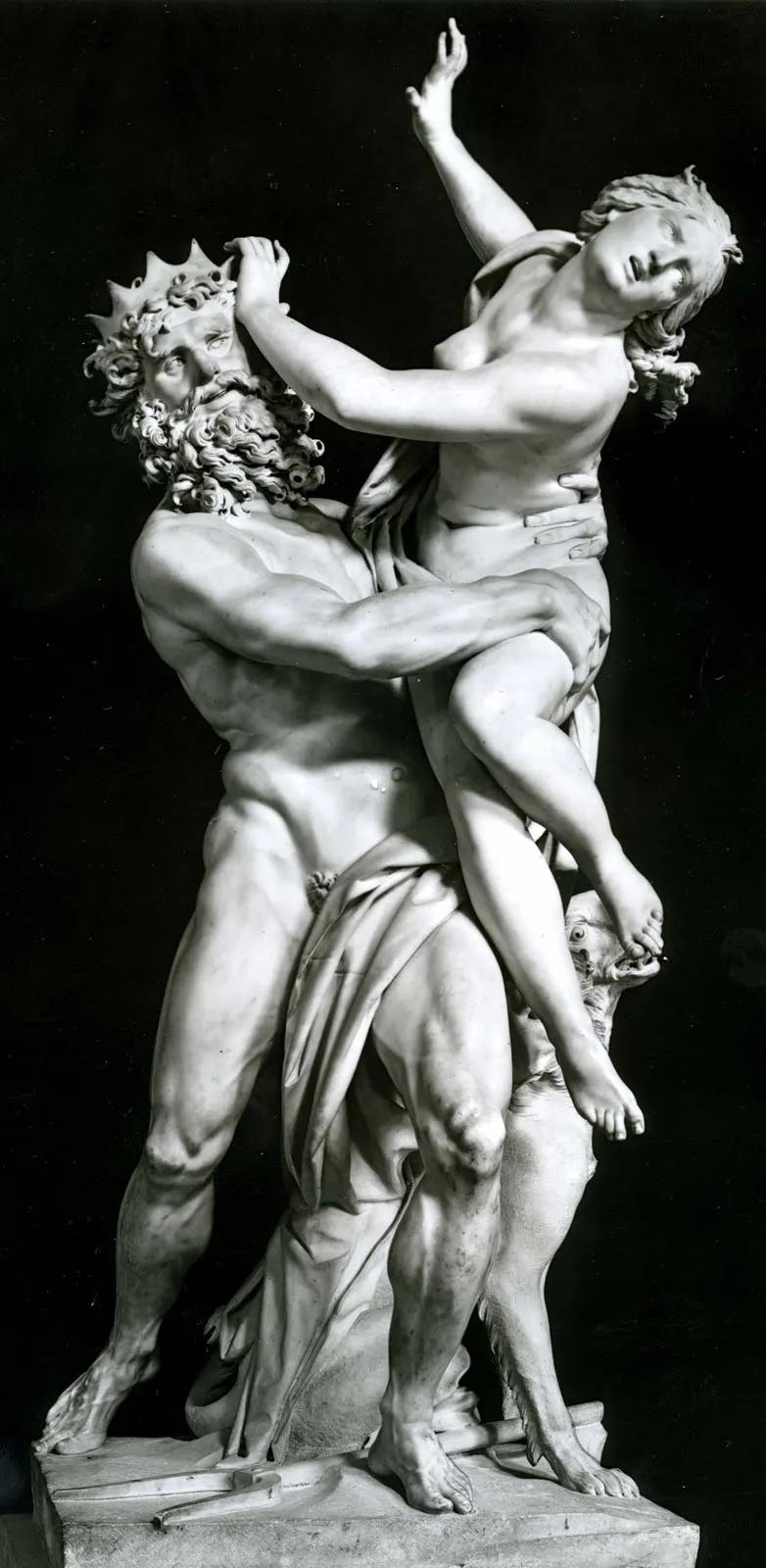

In an ancient myth, the goddess Cybele falls in love with Attis. Whether she is Attis’s mother is beside the point because Cybele’s title is the Great Mother (Magna Mater). Unfortunately, Attis is to be married to someone else — in Cybele’s mind, the wrong person. Cybele appears in her full splendor when the wedding is about to be commenced, and Attis flees to the woods, where he castrates himself and perishes there from his self-inflicted wound.

This is Cybele’s excessive maternal grasp on Attis, an example of the weight of excessive “lunar forces” preventing the reproductive power from reaching its proper height — this is the infantilization of the plant, the Earth Mother refusing to let her child grow up. This is a widespread experience.4

“The moon’s role is to carry light through the night and through the cycles of time, hence the goddess of the moon is Diana, deiu-ana. The moon’s role is akin to that of the hearth, that is, of generational continuity, of generation and generations. Women and the feminine are essential to generational continuity and are linked to the moon; whereas solar traditions are masculine. The ancestors go through the moon, it is said in the Upanishads and also in Plutarch's account of ancient Roman tradition.”5

The Zohar refers to the moon as the power of receptivity. When there are “excessive moon forces” there is too much receptivity and too little giving away. Without this “moon” quality, Mother Earth would die too much. Without feminine reflected energy, plants grown on the soil are cut off from their ancestors. Compost is ancestral energy for plants made from countless mother plants. Without this ancestral inheritance, plants are placed into dead soil and have to struggle without the inherited wisdom of their elders — much of what they do will be incorrect, and even where they get it right, they will be “reinventing the wheel.” This is our epoch. Many of us had no one to learn from, no inherited practical skills, no wise elders — but we threw ourselves into the work to become future elders through practical experience. Though in our times, it may seem improbable, there can be excesses in either direction, particularly in our small gardens where we can pretty easily overburden future generations with excessive maternal influences. There must always be a dynamic interplay between the past and the future, the earth and the sky.

Compost is ancestral energy for plants.

There is nothing wrong with Mother Earth herself, but when we give her too much desire, she refuses to let her children mature. As Goethe says, “Everything transient is but a parable.” Myths are the eternal living principle, embodied by everything that comes into and out of existence. Myths aren’t fanciful stories — they are archetypal (or fractal) patterns. Myths are the language of the universe thinking about itself.

For Steiner (and Goethe before him), the entire process at work in plants in the development of the seed is “male”, while the Earth is the female counterpart:

“It is not a case of the seed-vessel being female and the anthers of the stamens being male. In no way does fructification occur in the blossom, but only the pre-forming of them are seed…. For plants the earth is the mother, the heavens the father. And all that takes place outside the domain of the earth is not the mother-womb for the plant. It is a colossal error to believe that the mother-principle of the plant is in the seed-bud.”6

This does not really contradict the scientific labeling of pistils and stamens, but rather speaks on a vast ecological scale, expanding to a macroscopic view to help us encounter plants with a beginner’s mind. The plant is the child of the soil and the heavens, of Mother Earth and Father Sky. These are not primitive notions, but living ways of expressing how life really works. The interplay of yin and yang is always dynamic, and our cosmic grandparents must be as equals or plant development becomes one-sided. In a dry season, the Mother must be included more consciously with water and organic matter so that the plant has enough of its matrilineal heritage to grow up big and strong. In a wet season, the Father must be consciously introduced by pruning and cultivation so that air circulation, light, and warmth interact in a healthy way to produce sweet fruits.

Goethe describes in his own way the same dynamics of fertilization and what happens when there is too much of one of our spiritual great-grandparents:

“It has been found that frequent nourishment hampers the flowering of a plant, whereas scant nourishment accelerates it. This is an even clearer indication of the effect of the stem leaves discussed above. As long as it remains necessary to draw off coarser juices, the potential organs of the plant must continue to develop as instruments for this need. With excessive nourishment this process must be repeated over and over; flowering is rendered impossible, as it were. When the plant is deprived of nourishment, nature can affect it more quickly and easily: the organs of the nodes are refined, the uncontaminated juices work with greater purity and strength, the transformation of the parts becomes possible, and the process takes place unhindered.”7

These voices all describe the same thing. A plant must be deprived of nourishment, experiencing that it is running out, to produce flowers. This can be due to a lack of water, a lack of nourishment (“coarser juices”), or a combination of both. If “coarser juices” of soluble (salt) nutrients are too saturated, a plant cannot produce the refined nectar necessary for healthy flowering and fruiting. As Steiner puts it, “The plant is most salty in the root, above it gets less and less salty and the blossom has little salt.”8 There is a secret to creating fertilizers too: flowers have the least salt, leaves have a mixture, and roots have the highest concentration of what would be “coarse juices.” If we wish to hold plants back in the root and leaf stage, we would make fermented plant juices from those aspects of other plants.

If a plant (or a person) is given absolutely everything they need in excess, they languish in a vegetative state. For some plants, such as cabbage, we want to continuously nourish them to prevent them from bolting — we want pronounced leafy development and wish to inhibit flowering. Alan Chadwick describes the “law of the vision of the end.” Memento mori. When an organism senses its own mortality, its flowers begin to open. If an organism never feels like it will run out of resources, it remains held back in the leafy stage.

Steiner suggests, “We describe what happens in the womb as the workings of the moon.”9 When this “dark mother” influence is too strong, it corrupts the flower process; this is Cybele refusing to let Attis marry anyone else; this is the Earth Mother refusing to let her plant child grow up. But her child is not only hers, “For plants the earth is the mother, the heavens the father.”10 According to Steiner’s pedagogy, children should be spoiled (within reason) and allowed to play freely in order to develop healthy imagination (“will forces”). Children who are excessively restricted in their early years tend to become wildly unregulated later — they become “willful and weak-willed.” Some of the most restrictive households produce some of the most self-indulgent adults for this very reason: people who aren’t allowed to develop a strong will as children will not tend to possess the willpower to resist their own impulses as adults later. A plant that is not given enough organic matter (matter being a cognate of Mater, mother) may quickly mature but produce tiny sour fruits and hollow seeds.

Chadwick talks about “the Sun and the Earth and this marriage that creates atmosphere”11 and how “it is part of the destiny of humanity in particular, as the directeur of the orchestra” to manage this dynamic sensitively and dynamically. The human being is at the center of the medicine wheel, able to balance hot and cold, wet and dry, above and below. This art of directing and balancing the elements in a way to support life is elsewhere called alchemy, which is not about literal “gold” but about taking what is normally rejected as worthless, recognizing its value, and enhancing it. Someone else might describe this as developing a personal relationship with manure.

If there is too much of the heavy “ahrimanic” side of things, a plant is held back and stifled by the mother. If there is too much of the light “luciferic” side of things, plants rush to seeds, but the seeds are tiny and the fruits bitter. One is infantilizing, and the other is premature blossoming. One is too early, one is too late. But “fertility is the marriage” of cosmic and earthly, of father sky and mother earth. If one is too strong, there is no marriage at all. “[H]ypermasculine and hyperfeminine ideals can only come into being by overemphasizing some aspects of archaic cultures at the expense of others.”12

Steiner refers to freshwater springs as “eyes” of the earth.13 And flowers with their fresh nectar are like refined springs welling up from the coarser fluids of the earth.

When the mother’s grasp is too strong, the son is prevented from growing up. In the flower, the plant becomes liberated from itself. Owen Barfield calls the light ether the “etheric in the etheric,”14 which we can extend to the plant: the flower is almost a second plant that emerges triumphant from the green leaves.

We must prevent the arrested development of Attis if we want mature fruits. We must allow the plant child of Mother Earth and Father Sky to grow up. As a rule, Steiner himself warns against parents being their children’s exclusive teachers because it places too much of a one-sided parental weight on them — he also suggests much the same thing about nursing for too long.15 While both parents are needed, it is not merely Father Sky and Mother Earth, but the entire complex ecological world into which plants must be integrated.

“In mother’s milk we still have therefore astral formative forces that work spiritually; and we must realise what a responsibility rests upon us when the time comes to let the little child make the transition to receiving his nourishment directly for himself. The responsibility is particularly great for us today, since there is now no longer any consciousness of how the spiritual is active everywhere in the external world, and of how the plant, as it ascends from root up to flower and finally to fruit, becomes gradually more and more spiritual—in its own nature and also in its activity and influence. Taking first the root, we have there something that works least spiritually of all; in comparison with the rest of the plant, the root has a strongly physical and etheric relation to the environment. In the flower however begins a life which reaches out, in a kind of longing, to the astral. In a word, the plant spiritualises, as it grows upwards.”16

As the plant child of Mother Earth and Father Sky matures, it becomes more and more like the cosmic paternal principle.

I like to think of the forces given in the seed as a direct inheritance from the mother plant’s blood. The cotyledons are like the moist umbilical cord, which must dry and be cut for the newborn to become itself. The humus in the soil is mother’s milk to plants, composed of countless transformed remains. “Physically, the human being first feeds on blood in the mother's organism, then, when he emerges as an independent being, on milk – the sublimated physical animal blood. The sublimated physical plant blood is the sap of the flower and the honey that is made from it.”17 The Great Mother would wish never to cut the umbilical cord — and never to cease breastfeeding — and certainly never to let her son marry.

Steiner explains:

“The plant in growing from the soil in its year is at first really growing with the powers which the sun has given to the earth the year before if not earlier, for the plant takes its dynamics from the soil. These dynamics taken from the soil can be traced as far as the ovary, as far as seed development. We therefore only have a genuine botany that is in accord with the whole physiology if we take account not only the dynamics of warmth and light and of light conditions in the year when the plant is growing, but starting from the root base ourselves on the dynamics of light and warmth at least in the year before. We can trace this as far as the ovary, so that we have something in the ovary which happened the year before still active from the year before. If on the other hand you study the foliage, and even more the sepals and petals, you will in the leaves find a compromise, I'd say, between the dynamics of the year before and the dynamics of the current year. The leaves have in them the element pushing up from the soil and the influences of the environment. In petals the current year finally shows itself in its purest form. The colours and so on in the petals are not something old—they are of this year.”18

A plant’s initial physical form, particularly the first roots and cotyledons, is directly inherited from the mother plant. It then feeds on the reflected sunlight of yesteryear (humus). Humus is mother’s milk to plants — nothing needs to be chewed. Like milk, good colloidal humus is “almost liquid life.”19 Humus is the dimmed reflection of the forces of the sun. Organic matter is always composed of other mother plants. Moonlight is reflected sunlight. Humus is the sunlight of yesteryear on its way back to the cosmos. So-called “lunar forces” are a concrete and recognizable process. Thinking mythologically does not mean we need to become superstitious or irrational.

Plants absolutely need vitality in the soil, but too much of anything — even good things — is problematic. “Were only the etheric body to work, then the plant would unfold endlessly leaf by leaf; this is brought to a conclusion by the astral body. The etheric body is muted by the astral.”20 Similarly, an over-nourished body closes off the chakras — higher faculties are impossible if the flesh is overfed, just as frequently nourishing plants inhibit their flowering. Anyone who has experienced an over-fertilized “rank patch” will have seen leaf after leaf — but no flowers. In the human being, this will look like constant juvenile activity but no developmental progress.

Humus is the sunlight of yesteryear on its way back to the cosmos.

The emergence of the flower is experienced as a defeat by the leaves. But the flower is a triumph for the whole plant. The Great Mother would wish that none of her children would have to die — or grow up. But grow they must.

The plant’s development embodies the mythical life of Attis, who is raised by the Great Mother, and his physical form is inherited from her (“'the powers which the sun has given to the earth the year before”) dressed in his mother’s clothes (“you will find in the leaves a compromise”), and in the mature plant releasing nectar from its blossom, we find Attis bleeding (“in petals the current year finally shows itself in its purest form”). The blood of Attis enters the earth sacramentally, and he is resurrected annually.

Remember the wedding Attis was to attend? The name of the woman to whom he was betrothed? She is someone famous for her own annual cycle.

Her name? Persephone.

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture VI (GA327, 14 June 1924, Koberwitz)

Steiner himself describes his indications in the foundational Agriculture Course as trying to articulate spiritual-scientific truths in aphorisms — pithy (but useful) generalizations. We cannot cling pedantically to such pithy generalizations without becoming fundamentalists. We must realize these fragmentary images point to a greater wholeness we can only know through direct experience. Steiner’s words are vectors full of vital force, not final conclusions. Like seeds sown, his insights were never meant to remain seeds. A seed must die in order to bear fruit. They should motivate action (and further elaboration) if they are alive in us. Steiner’s words may inspire us, but should never restrict us: “We shall have to attempt to put into aphoristic form some of the Spiritual Scientific conceptions concerning the enemies of agriculture, animal and vegetable, and which are called the diseases of plants. Now these matters can only be studied in concrete cases; they must be dealt with specifically; there is little that can be said in a general way.” - R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture VI (GA327, 14 June 1924, Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture VI (GA327, 14 June 1924, Koberwitz)

My own mother — in her own words — answered the question: what is the hardest thing you’ve ever had to do? “Letting my children grow up.”

Arthur Versluis, Religion of Light, pg 20

R. Steiner, Man as Symphony of the Creative Word, pp. 128-129.

Goethe, Metamorphosis of Plants, P30

R. Steiner, Cosmic Workings in Earth and Man, Lecture I, (GA352, Dornach, 9th February, 1924)

Rudolf Steiner, From Beetroots to Buddhism, pg 160.

R. Steiner, Man as Symphony of the Creative Word, pp. 128-129.

Alan Chadwick, Performance in the Garden, pg 127.

Arthur Versluis, Religion of Light, 23.

R. Steiner, Cosmic Workings in Earth and Man

“In the Four Ethers of which Rudolf Steiner has said so much, we find again the four principles of which man is composed. We find physical, etheric, astral and ego in the Warmth Ether, the Light Ether, the Chemical Ether or Sound Ether and the Life Ether respectively.

Here again, in the case of the Light Ether, we get that special emphasis – of the principle within its own principle. Light Ether is the etheric in the etheric. Without going into the question how far it is possible to call any part of light “physical”, I suppose, then, we are not far astray, if we think of this light from the sun that comes flooding in on us through our eyes, when we wake in the morning, as a sort of gateway through which our consciousness can enter into an experience of the etheric world – if we think of light as, shall I say, the etheric par excellence. And that is why I begin by considering our experience of light from this point of view, by considering our experience of the etheric cosmos.

We must, however, distinguish experience of the etheric from ideas we may form about the etheric before we have any experience. These ideas are likely to be – in my case they certainly were – not truly ideas about the etheric at all, but only ideas about the effects of the etheric in the physical." — Owen Barfield, The Light of the World.

The practical limitations of real life don’t always provide us with ideal conditions, and the excesses of parental involvement may often be preferable to too little parental participation.

R. Steiner, Curative Education, Lecture XII, (GA317, 7 July 1924, Dornach)

R. Steiner, (GA91, 2 October 1906, Landin)

Rudolf Steiner, Physiology and Healing, pp. 85-86 CW314.

R. Steiner, Human Being as Body, Soul, and Spirit (GA347, 13 September 1922, Dornach)

R. Steiner, Stuttgart, February 8, 1909, GA98