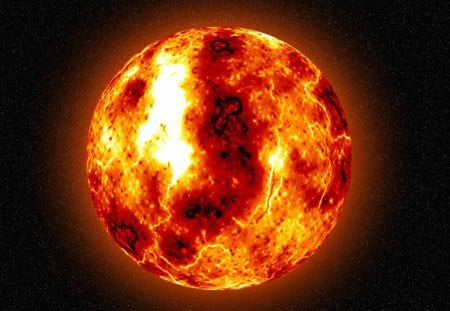

In a prehistoric epoch, the earth was too hot for water to condense into rivers, lakes, or oceans. Instead, other compounds like silicon were fluid. We might say molten but the entire earth did not yet have a solid crust. The earth was once too hot for water to condense into rivers, lakes, or oceans. As Steiner says, “As long as the earth was soft, such forces were still in it.”1 When the earth hardened, those activities — relatively speaking — became locked up. With certain preparations, such as the horn silica, we liberate these and make them available to live again, but in general, these forces are not nearly as active as they once were.

Under different conditions, chemistry behaves in radically different ways. One can almost imagine molten glass raining down in winter. The earth experienced a sort of summer and winter, with variations in temperature enough to solidify quartz and melt it again. In such a world, H2O could not exist except perhaps as isolated molecules in a gaseous state.

For anyone who’s performed the childhood experiment of warming water, dissolving sugar, and then cooling the solution, you see spontaneous sugar crystals arise. Most of the earth’s crust is silica – quartz. But when the earth was much hotter, that quartz would have been molten. Only by cooling enough did it crystalize out of solution. Artist Larry Young suggests, “The crystal is a resurrected creative deed from the far distant past.”

As the earth cooled over eons, these silicate crystals remained in a more permanent solid state. Eventually, water as we know it became the fluid element condensing in pools and rivers and between the crystalline crust of the Earth. We have a picture of silicon dioxide having been molten and crystallizing. In this image, Rudolf Steiner tells us we see something of a foreshadowing of the possibility of plant growth. It is as if crystals are an earlier incarnation of the archetypal plant, the Urpflanze appearing in the only way that it could because carbon-based growth forms were impossible. In this prehistoric epoch, silicon was the carrier of living forces, before carbon would have its golden age.

While the earth was still molten, the living (dynamic) potential at work there was still unfolding. Soil as we know it is far less active than the primitive earth in its mobile molten state. Steiner says, “When you go out to the mountains to-day and find granite there, or gneiss — which differs from granite in being more rich in mica — they are the remains of this ancient giant plant… And thus to-day you have the mountain ranges. For our hardest mountains originated from the plant nature, when the whole earth was a kind of plant.”2

What crystallized out of the primordial earth was quartz, and this image is maintained (in microcosm) by plants: “If you observe a plant to-day and enlarge it, you find even now that it resembles the mountain formations outside. For the universe only acts on the plant as a whole; its minutest parts are already stone.”3

If we take a step back, anything that unfolds into physical form did so by using energy and that energy “dying” into manifest form. Steiner reminds us that all plant growth is a process of devitalization — the crystallization of growth is the discharge of potential energy into condensed form, a dying of life potential into actuality. Steiner says: “We find the strongest life force in the root nature, and there is a gradual process of devitalization from below upward.”4

This is how quartz belongs to a transitional stage between primordial chaos and living form. As John Ruskin writes in Proserpina, “A flower is to the vegetable substance what a crystal is to the mineral.”5 When the world was a fluid primordial soup of minerality — and Steiner emphasizes that “water, too, is mineral”6 — out of this fertile chaos would birth crystals as the spiritual forerunner of the kind of emergence that would later express as flowers. In this sense, quartz silica is another flower process, albeit one of the realm of minerals. Quartz “died” out of a dynamic living fluidic state and became a form transparent to light, something that flowers would later do out of the sap of plants.

One can imagine that the world of quartz had hardened, and these floral crystals were covered in dew as water condensed from the atmosphere. On these moistened silica florets emerged a new form of life as a transition between the crystal world and the plants we know today: giant equisetum towered.

These plants could tolerate constant humidity in the atmosphere and stagnant water perpetually around their roots. They could eat rocks, and themselves embodied a new kind of receptivity to the light of the cosmos. Though they had no true leaves, they could photosynthesize. But as these great primitive treelike growths grew and died, they piled up one on top of the other until there were vast deposits of these transitional “mineral-plant” trunks. But without something to decompose them, they kept accumulating. Out of this emerged something new: in the anaerobic remains of these giant transitional growths between minerals and tender plants, fungi emerged as feeders on the forces contained in this woody “mineral-plant” substance.

With each unfolding mushroom, which Steiner calls “unformed flowers”, is a release of so-called “moon forces” of sour, acidic, peat-like organic matter. What are “moon forces”? The Zohar describes the Moon as the power of receptivity. Too much receptivity, and you get imbalanced growth, just like if you overeat, you harm your health. When there is too much growth force in the soil, it must be released or used up by something else so it doesn’t overwhelm our tender plants. Mushrooms rush prematurely to “blossom,” producing spores, and this eruption discharges lunar excesses from the soil. When there is an excess of this sour mineral-plantlike substance, we need to encourage an organism that is like an animal but also like a plant: fungus. We want the animal-plantlike fungi to be in a hurry, so they use up these forces before they harm our plants. Steiner says we should ensure our meadows are “full of toadstools” because they occupy the same space as pathogenic entities — or rather, they consume the same food for which pathogenic entities hunger.

Mushrooms use as food what would otherwise be a poisonous excess for our plants.

As earthworms consume excessive ethericity and work as “release valves,” according to Steiner, mushrooms similarly consume excessive “moon forces” and release them in their bursting from the soil. Mushrooms use as food what would otherwise be a poisonous excess for our plants.

Rudolf Steiner says we must make sure our meadows are full of toadstools. So how do we remind mushrooms of their primordial history and encourage their proliferation? A tea of Equisetum is for us a way to discharge excessive sour organic matter formed by a “wet winter followed by a wet spring” especially by encouraging lunar-governed mushrooms to proliferate. When we use Equisetum on our siliceous souls, we restore and recapitulate the evolution of the earth. Especially on deadened soil that has been reduced to inert dust, Equisetum as a tea restores the necessary transitional living forces between quartz and plants upon which fungi thrive, making way for balanced living soil.

Equisetum is commonly described as having an “antifungal” effect on our plants. While this is true, Lloyd Nelson has also observed a paradoxical phenomenon: using Equisetum as a tea sprayed over the soil encourages the mass proliferation of mushrooms. As the Australian Biodynamic website says, Equisetum “has the effect of encouraging the growth of beneficial fungi in the soil in the fermented form.”7 How can encouraging fungus be reconciled with Equisetum as an antifungal agent?

It is this: fungi in the soil consume and discharge the very forces that would poison plants and otherwise give rise to fungus on the poisoned leaves. An inadequate level of fungus in the soil, paradoxically, leads to pathogenic fungus above the soil on plants. Similarly, inadequate habitat for birds makes them appear as more severe pests.

In biodynamics, we strive to remain “within the realm of the living,” which means we remain in the realm of becoming. Once something has settled out of life, it hardens, condenses, and resists change — its living potentiality has died into actuality. So we help restore to the soil its ability to become something else by using things full of potential.

May our old habits release their attachment to forms and decompose into humus within us. May we grow in our time and then nourish the next generation in our time as well. May the remains of the past ever provide fertile soil for the new.

R. Steiner, Cosmic Workings in Earth and Man (GA349, Dornach, 17th February, 1923)

R. Steiner, Cosmic Workings in Earth and Man (GA349, Dornach, 17th February, 1923)

R. Steiner, Cosmic Workings in Earth and Man (GA349, Dornach, 17th February, 1923)

R. Steiner, Fundamentals of Anthroposophical Medicine (GA314, 28 October 1922 p.m., Stuttgart)

John Ruskin, Works of John Ruskin, Proserpina, (University of California, 1885) pg. 49.

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture VI (GA327, 14 June, 1924 Koberwitz)

https://biodynamics.net.au/product/equisetum-arvense-508-fresh/

Thank you for this excellent expansion of and follow up to the concepts introduced in Lecture 1 of the Agriculture Course that we are studying. Your explanation, like Biodynamics in the kingdom of nature, truly stays in the living in the realm of ideas.

Fascinating. I will make a point to inoculate wood chips in our gardens with mushroom spawn this year- and additional crop as well as “using up” the over abundance of etheric forces……. Love the practical info!