“Observation is an old man’s memory.” - Jonathan Swift

In biodynamics, we must begin where the plant begins: with the root. In the development of a plant, the first thing to emerge is its root, followed by its green cotyledons, and finally by its flower with its fruit. In this trichotomy, we see one aspect growing downward and two others growing upward. There is nothing revolutionary about suggesting that the root is light-hating, whereas the green growth and blossom are light-loving. What initially emerges in the plant is its reaching down towards the past, almost as if the root expresses a recollection of its past for the plant. The seed germinates by beginning with the grasping reaching for the past, as an infant reaches for its mother. The seed can be seen as belonging to the continuity of the past into the future, the root aspect reaching the top of the plant. As Steiner says, the “dynamics taken from the soil can be traced as far as the ovary, as far as seed development.”1 The seed is almost like a pinched-off piece of cambium, able to take root as a new incarnation of the plant, because it maintains an inner kinship to the mother plant’s root, reaching back in time.

This living power to grow, adapt, and proliferate is goodness itself. By contrast, what we call “evil” thwarts harmonious proliferation by preventing flowering altogether or starving the seeds of their connection to the past. But real seeds, life itself, unfolds endlessly. You can eradicate all the life in a field and the very same season it will burst forth with green vegetation. You can spray biocides and life adapts.

Consider the humble dandelion capable of breaking through asphalt. Our morally worthless deeds are like pavement, but our good deeds are like dandelion seeds. Pavement must be maintained by effort. Left by itself, vegetation wins over dead asphalt. One dandelion seed does not create just one more plant, but rather it reproduces exponentially. Even though the power to act at all comes from elsewhere, the value of our good deeds outweighs the bad, because what is good is alive and proliferates.

A true gift of kindness, out of what is justly earned, is not merely a karmic benefit to ourselves, but an unfolding fractal of goodness. As Lewis Hyde observes in The Gift, to remain alive, a gift must keep being given.2 By contrast, erosion and parasitism depend on what is built up by the life they follow but they are reactive, devoid of initiative. The growth of inorganic evil follows on the heels of life's unfolding exponential growth.

Inside each germinating seed is a “dark” hunger inherited from the past, redeemed through the production of yet more life and newness. The source of existence is “dark” because it is so bright it is blinding, rather like staring into the Sun. As it says in the Zohar, “The first impulse of emanation is described as botsina de-qardinuta, ‘a spark of impenetrable darkness,’ so intensely bright that it cannot be seen.”3 Thus, the Father is only accessible through the Son, who dials down the presence of divinity so that we can retain our individuality in the presence of God. For, as the Father says, “no one can see me and live.”4 T.S. Eliot harmonizes with this, saying, “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.”5 When Krishna reveals his overwhelming “formless form” in the Bhagavad-Gita, Arjuna begs to have the more palatable image of his beautiful blue cowherd returned. While in the complete absence of light, we are blind, when a light source is too bright for our organs of perception, the light is blinding. We can only assimilate what we are prepared to receive. In biodynamics, it is our task to prepare the soil and plants to be receptive to what the cosmos has to say.

Image by Stewart Lundy, All rights reserved. Used by permission.

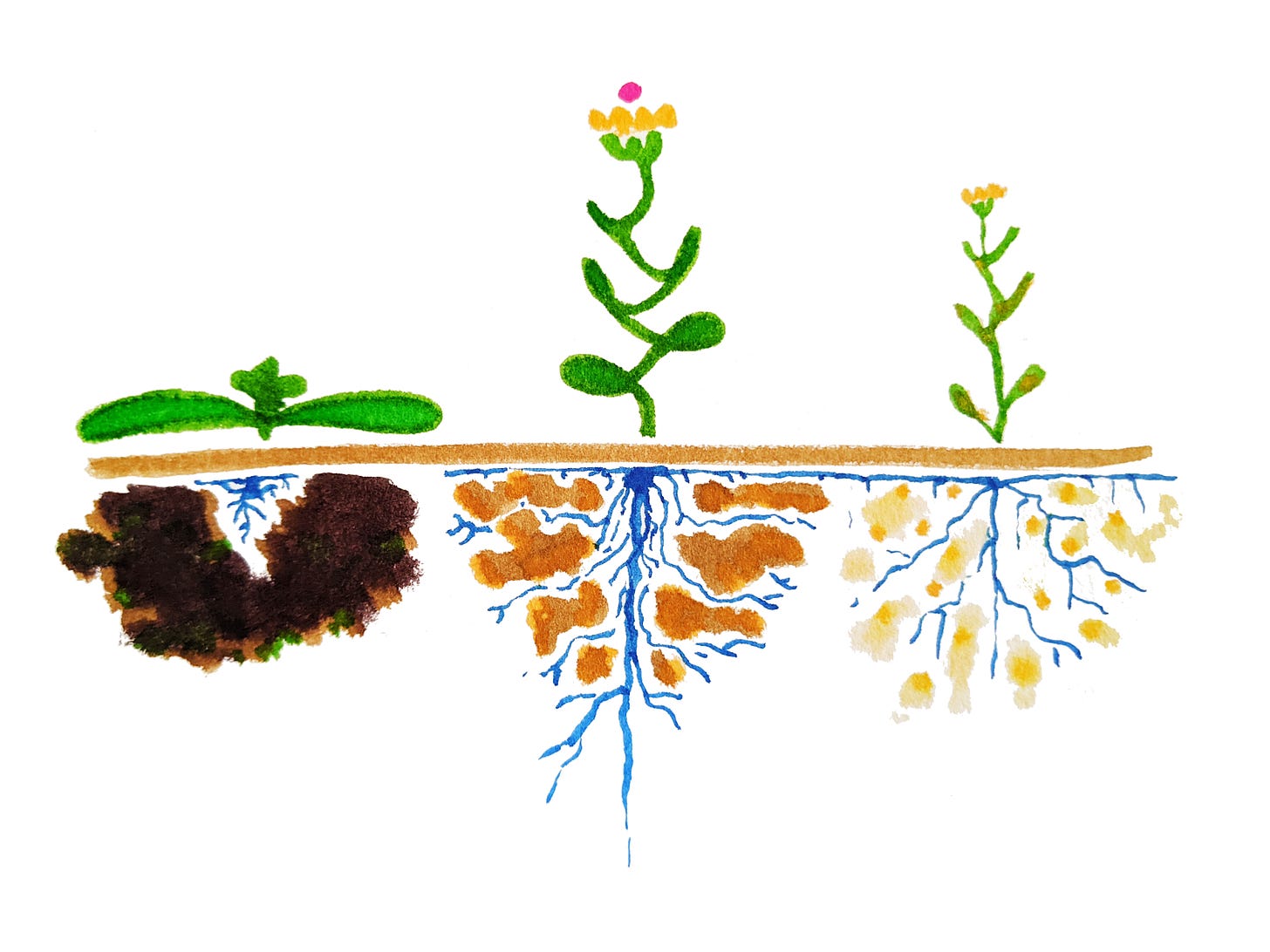

Image: Left: overnourished plant; Middle: balanced plant; Right: undernourished plant.6

Going further, an unknown author suggests that “[e]xperience teaches us that there are two kinds of darkness in the domain of consciousness. One is that of ignorance, passivity and laziness, which is ‘infra-light’ darkness. The other, in contrast, is the darkness of higher knowledge, intense activity and endeavour still to be made—this is ‘ultralight’. It is a question of this latter ‘darkness’ in instances where it is a matter of resolving an antinomy or finding a synthesis.”7This conciliatory movement towards reconciling what is separate belongs to our effort. As a candle has an imperceptible light at the source of its illumination, so a plant emerges out of the dark, radiating almost etheric flames back to the cosmos. But like a candle, we don’t want the plant to expend itself too quickly nor do we want it to smolder too dimly.

To experience the candle’s flame, an analogous process must arise within us: the dark brightness of empty consciousness must be kindled and meet the external image. Without the inner light of consciousness to encounter the outer phenomenon, the mechanism of the eye can see nothing. In Steiner’s explanation of cognition in Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path, this is the process whereby a concept grasped by intuition is united with a sense-perceptible object (a “percept”). The marriage of unifying ideas with external perception is cognition.

Similarly, a plant grows out of darkness and spreads its leaves to encounter the external light. Receptivity to that light, however, belongs not merely to a dead mechanism but to the inner life of the plant. If a plant is overnourished, it is not receptive to the subtleties of light, but if a plant is starved, it cannot do anything fruitful with the light it enjoys. So, a soul addicted to sensual pleasure is not receptive to the spiritual meaning that belongs to the sense-perceptible world because the soul cannot meet it. As St. Thomas Aquinas says, “The reality of things is their light.”8 If I only notice the outer effects of a candle—that it is hot or that the room is illuminated, but fail to recognize the candle for what it is, that is what it is like to live in the world of superficial appearances, the world of Mephistopheles, the attachment to which is called maya. Misunderstanding a candle can mean things end in flames. Appearances themselves are not the problem, but rather our fixation on them as if surfaces are where meaning begins and ends.

Misunderstanding a candle can mean things end in flames. Appearances themselves are not the problem, but rather our fixation on them as if surfaces are where meaning begins and ends.

Image by Stewart Lundy, All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Image: Candle with the dark source of light at the heart of its flame.

To be receptive to the life streaming in from the cosmos, the soil itself must have life. As Empedocles suggests, like perceives like. If we wish the soil to be receptive to life, we must make sure that it is not dead. Thus, the first step in biodynamics is enlivening the soil out of which the plant will emerge so the plant’s roots do not enter a soil devoid of the memory of life.

We must supply the blush of vitality from formerly living things to deadened soil, particularly in the form of manure and compost. The vitality available in compost to enliven soil belongs to the recent past, for which the root in particular is hungry. As part of re-enlivening the soil, we use horn manure, which restores a dark ember of liveliness to the earth. This is followed by horn silica, which fans the etheric flames of the plant to rise out of concealment and into articulate form. Goethe speaks to the heart of fertilizing in The Metamorphosis of Plants:

“It has been found that frequent nourishment hampers the flowering of a plant, whereas scant nourishment accelerates it. This is an even clearer indication of the effect of the stem leaves discussed above. As long as it remains necessary to draw off coarser juices, the potential organs of the plant must continue to develop as instruments for this need. With excessive nourishment this process must be repeated over and over; flowering is rendered impossible, as it were. When the plant is deprived of nourishment, nature can affect it more quickly and easily: the organs of the nodes are refined, the uncontaminated juices work with greater purity and strength, the transformation of the parts becomes possible, and the process takes place unhindered.”9

If a plant is supplied with too much nourishment, the root grows lazy and the plant languishes, producing only leaf after leaf. As Steiner says, “Were only the etheric body to work, then the plant would unfold endlessly leaf by leaf; this is brought to a conclusion by the astral body. The etheric body is muted by the astral.”10 In winter we see cabbage attracted more by the reflected warmth from the soil than the direct sunlight—its leaves grow horizontally. In the human being, if we only pursue conditions that feel comfortable, we will never be challenged, and we will, so to speak, vegetate like a dish of mold. Suppose we transplant after the summer solstice when the sun is at its zenith in the sky. In that case, we are not likely to see good root development or succulent leaves: plants tend to rush to flower under the excessive influence of the summer sun because they are not mature enough to receive and contain those astral forces in lush leaves or sweet fruits. Similarly, plants that grow up in a greenhouse in spoiled conditions without healthy challenges grow deceptively large but are inwardly weak because they are inexperienced. If transplanted too abruptly, tender plants suffer from shock when encountering unfiltered reality for the first time.

The astral influences of summer stimulate the discharge of etheric life potential accumulated in the soil. As the sun’s warming rays make the fog rising from a field dance in various forms, the etheric and the astral, performing together, give rise to the physical expression of “etheric formative forces.” Astrality uses up (or discharges) ethericity. As such, we do not begin by supplying the soil with more astrality, but rather replenishing the soil with ethericity from above.11 One does not plug a refrigerator into the socket of a house without electricity and expect it to work. Likewise, one should never transplant into dead soil. Since it does little good to fan a fireplace with no flame, we must start by supplying fuel for warmth and life. If a plant is not mature enough when these forces reach their full force, the plant cannot contain them as nourishment. Instead the plant gives up and rushes to flower. As children should be pampered in their earliest stage (but not ruined by sustained overindulgence), we begin initially by indulging young plants. We give them more than they need so they can develop the proper “will forces”—the accumulation of which offers a significant portion of nourishment.

As a child cannot simply be born and then abandoned but must be nursed until it is weaned, a plant also should not simply be dropped into soil devoid of life. Steiner says in the Agriculture Course, “manuring consists in a vivifying of the soil so that the plant may not be planted in dead soil. A plant will more easily develop from its own vitality what is necessary for fruit formation if it is planted in something already alive.”12 This is why we begin with enlivening the soil. As an infant must be nursed with milk, we must supply the soil with the kind of nourishment tender toothless nascent roots can assimilate. A mother bird must grind up food for her offspring. This is the kind of food we must introduce to tender young plants who have not, so to speak, developed “teeth” to chew tougher foods. Plants must be delivered nourishment in a suitable form so they can absorb it and discharge it as kinetic energy as they grow into their specific forms.

If it produces fruit at all, a plant emerging from excessively decadent darkness will tend toward “fire” diseases, where the leaves serve as a suitable substrate for infections. It is often better for an organism to have slightly too little earthly nutrition rather than too much. Steiner wrote, “most people are thoroughly convinced that the more they eat, the better they are nourished. Of course it is not true. One is often much better nourished if one eats less, because then one does not poison oneself.”13 By contrast, if nourishment is deficient, a plant will run out of energy and rush to flower, but its fruits will tend to be minuscule, and its seeds may even be hollow.

Image: Left: Rudolf Steiner’s 1924 watercolor depiction of the Urpflanze (the archetypal plant); Right: Steiner’s sculpture of the Representative of Humanity.

In extreme asceticism, practitioners attempt to starve out the lower bodily impulses, often aspiring to eradicate all animal desires. It is as if they wish a lotus could blossom out of something other than mud! But as they say in the film I Heart Huckabees, “No mud, no magic.” As karma from before is the basis of our conditional freedom now, the residue of the past is the fertile soil of today. No miser wishes to benefit anyone, but his money is nonetheless distributed after his death, and society benefits despite his intentions. Our task is to benefit others willingly while we are alive with our sweet fruits and hold the door open to new life, not merely supplying unconscious compost, though we necessarily contribute to that as well.

Our task is to benefit others willingly while we are alive with our sweet fruits and hold the door open to new life, not merely supplying unconscious compost, though we necessarily contribute to that as well.

Severe asceticism forces open the inner blossoms of the human being. This feeds the honeybees of the invisible, but there are more mouths to feed with fruit. The spiritual ideal that anthroposophy offers is neither vegetating as an overnourished plant, nor bolting as a starved plant. As Steiner says, “Anthroposophy is never fanatical.”14

A sensible farmer always seeks balance and, instinctively, is not a hot-headed revolutionary. He can’t afford it! His profit margins are too narrow to risk them on anything uncertain. As such, “only those things should be opposed,” Steiner says, “which rest on completely false assumptions and are the outcome of the modern materialistic conception of the world.”15 This is why, in biodynamic agriculture, we reject nothing that has shown itself to work and be compatible over time with openness to ever-new life. One might even go so far as to say that all agriculture is already “biodynamic” to a degree to which all farming necessarily conforms to the laws of life if it can produce nourishing food.

Image: the heart of a living being is off-center.

As the human heart is not quite in the middle of the chest, the Aristotlean “golden mean” between extremes is always slightly off-center. Excellence is not the lukewarm dead center of stale compromise. We may have cold-bloodedness on the one hand and hotheadedness on the other, but the balance between these extremes is not lukewarmness but rather heart warmth—not so cold it freezes, not so hot that it burns, but certainly also not tepid.

Excellence is not the lukewarm dead center of stale compromise.

A prematurely flowering plant with its delicate fragrance is closer to ripened sweet fruit than it is to an overnourished plant only capable of producing leaves, but one error must be overcome while the other must be tempered and thus redeemed. If making tea, we take cold water, bring it to a boil, and let it cool to the perfect temperature. The weight of the dead facts of the past must be raised up, while the infatuation with the imagined future must be tempered.

Image: Christ Appearing to the Magdalen as a gardener, after Dürer

If we work with a dark heavy soil, that soil must be lightened with careful cultivation. If we are working with a light airy soil, it must be darkened with the right amendments to become receptive to the instreaming influence of the cosmos. The soil is like the eye: it can only perceive light because of its inner darkness. As Meister Eckhart says, “It is in the darkness that one finds the light.”16 Similarly, if a soil has too little air, the metabolism of organic matter is restricted. If a soil has too much air, the metabolic fire burns too quickly. Fundamentally, any soil that has lost its vitality must have it replenished from elsewhere else. We must borrow vitality from the surrounding living environment and introduce this life to deadened soils

There are two poles of a plant: the light-shunning, and the light-loving. In scientific terms, these are called phototropic and photophilic, respectively. When we use cover crops, we kill back the cover so that its root system dies into the soil. These roots are light-hating and, considered in themselves, hunger for the dark world of fallen water, condensed mineral salts, and decomposing humus. As Steiner says, humus is a “lightless”17 activity. If considered by themselves, the roots hungering for the dark earth do not “intend” to benefit the rest of the plant. The benefits for the rest of the plant are something that is wrested from them by a rival impulse to return to oneness. As Steiner says, “Whereas the Luciferic tendency is always towards unification, the fundamental tendency of the Ahrimanic principle is differentiation.”18 In the branching of the root, we see ramification in all directions, whereas above we see more sculpted forms and a tendency towards devitalization.

The roots of legumes do not exist to be generous to us but rather to store up what they need for themselves. A legume crop, if allowed to go to seed, can result in a net loss of nitrogen available in the soil because it uses it up for its own fruiting process.19 These roots are concerned with drawing things into themselves for their own purposes. This sheds some light on why Alan Chadwick recommends killing back a cover crop when 20 percent of it has begun to blossom but before any of it has gone to seed. If we kill back a green cover crop when about 20 percent has begun to blossom, we retain what the plant has accumulated for itself. As Steiner says, “the intention of Lucifer and Ahriman is to prolong this budding and growth indefinitely.”20 Namely, the two work without reproduction or openness to evolution. Mephistopheles is content with ever-assimilating growth forces, Lucifer with ever budding and discharging, neither particularly troubled with providing nourishment for others in the present. The “luciferic” impulse is the discharge of potential energy back to the cosmos without fostering another generation of life. The “ahrimanic” impulse is the pure accumulation within itself, in a miserly fashion. The “christic” impulse allows the return to the cosmos by way of sweet fruit and viable seed production, which holds the door open for adaptation and unfoldment of ever-new life.

If we want to increase the potential energy reserve of the soil, we enhance the dark aspects first. If humus were left to itself and had nothing sandy, it would tend to become anaerobic like a peat bog. But with the addition of sandy materials (and the oxygen it allows into the soil), accumulated humus can begin to decompose, releasing its stored energy. Steiner describes humus as “substances in course of decomposition, bear[ing] etheric life within.”21 When light-bearing siliceous materials like sand are present, pockets of air are maintained through the soil, accelerating the decomposition (and therefore radiation of etheric vitality). For example, a light sandy soil quickly burns through organic matter, whereas a heavy clay soil does not. Why does a fire burn faster in open air? Because of the presence of oxygen. Why does humus burn off faster in sandy soil? Because of the presence of oxygen.

As a plant matures, the cotyledons wither and fall off as an umbilical cord withers and falls off an infant. It is as if these cotyledons are an etheric tether connecting the new plant back to its mother. At a certain point, the plant must become more independent. The cotyledons fall off, and the soil suckles the plant.

For the first six days or so, the plant grows primarily from what the mother plant gives it within the seed. It also, obviously, needs water and warmth, but its direct dependency on light is not initially fully established. Initially, sprouts can grow healthily in the dark. By the seventh day, it is as if the generative impulse pauses and now the plant now hungers not only for what it has already received from the mother in the seed but now directly desires the earthy element itself.

When we make compost, it is as if we have placed our hand on the wheel of time and sought to retain more power in one spot than would normally accumulate. Compost is a pile of all sorts of living materials in various states of decomposition. This potential for ongoing decomposition gives vitality to the compost pile. But this ongoing decomposition also makes manure an especially Mephistophelean aspect of farm life. Nonetheless, Mephistopheles still serves the greater good. Steiner shares, “For love to reach its highest goal, the love of all, it must pass through the love of self. In Faust, Goethe rightly causes Mephistopheles to say: ‘I am an aspect of the power that always intends evil, and always creates good.’”22 Noxious weeds may grow big in our gardens, but when they are harvested and made into excellent compost, their value is recycled to feed our crops. Whatever residual value of our less fruitful deeds becomes compost to feed other souls in the creative hands of others.

In this world, baser selfish love always precedes noble, selfless love. In a way, one must first develop a self to become selfless. As Hans Urs von Balthasar says, “Do what you will, you remain a captive of love.”23 Even what we do out of pure egocentric egotism, will nonetheless be transformed by the redemptive creativity of others, for forgiveness is always creative. Those who recognize this truth in a luciferic manner will tend to imagine that everything we do is always already forgiven, neglecting the real burden that our actions put on others. The proper response is the recognition that everything we do has unintended consequences and that the unseen grace of others constantly supports us. Nonetheless, one must have something in the first place to be generous.

There’s something selfish about making a compost pile. We take what would normally cycle through nature much more quickly and put our hand on the wheel of life, and ask it to linger a little longer with us for our own purposes. As Ehrenfried Pfeiffer notes in The Face of the Earth, harvest festivals used to be times of mourning and fear of having “stolen” from the gods what we stored up in our granaries. A compost pile is vitality we have taken from elsewhere and accumulated in one place. The life of a compost pile is somewhat plantlike, feeding off the life potential of the ingredients we add to it. Everything about humus made in a compost pile is incredibly transient. If you leave humus out in the sun, it quickly turns to dust and most of its vitality is gone. The compost pile itself embodies Mephistophelean disintegration, whose impulse is to separate out a purely material life on earth without even a hint of luciferic aspiration towards the light. As Steiner says, “Mephistopheles is a stranger to the realm of the Eternal.”24 This is because, with the philosopher Avicenna, we recall that the first emanation from God is the world of ideas. Mephistopheles, clinging entirely to the realm of the transient, refuses to see that “Everything transient is but a symbol”25 of something eternal.

Everything about compost is a process of transience, of one thing turning into another without a unifying cosmic formative principle. Composted manure is chaoticized material shorn of its cosmic organizing principle: what remains is life potential minus a directing impulse. In compost, the original plant ingredients are no longer a plant, but the unmoored qualities of those plants remain. This unorganized nature of composted manure gives it plasticity for the Spirit to perform its creative expression. Creativity can operate on this primordial formlessness: “Now the manure mingles with the soil; it is a return of beings into Chaos. Chaos is working in manure, in all that is cast out; and unless, at some time or other, you mingle Chaos with the Cosmos, further evolution is never possible.”26

“Now the manure mingles with the soil; it is a return of beings into Chaos. Chaos is working in manure, in all that is cast out; and unless, at some time or other, you mingle Chaos with the Cosmos, further evolution is never possible.” - Rudolf Steiner

Whereas Mephistopheles represents an impulse towards fragmented separateness, Lucifer represents the impulse towards a generalized unity erasing difference; but real life arises in the impulse between these two. Whereas the dark element in the soil wants to assimilate too much, the light element wants to return the light completely unchanged. As Sir Albert Howard says, “The wheel of life is made up of two processes—growth and decay.”27 But wherever there are two, there is a third balancing and directing these tendencies.28 It is not our task to be absorbed into the darkness or dissolved into the light but to strive in service of renewed life.

Steiner says in the Agriculture Course that “Fundamentally all plant growth is slightly parasitic in character; it grows like a parasite on the living earth.”29 This so-called parasitic quality of plants means that they depend on the kind of formless vitality accumulated out of the past within the soil. Anywhere you see the word “parasitic” you may read Ahrimanic or Mephistophelean. As such, Steiner refers to bacteria as “ahrimanic” because they feed off life they did not create. As a rule, in biodynamics we do not say that a compost pile is alive because it has bacteria but rather say that a compost pile has bacteria because it is alive. When we use cover crops or build compost, both aim to bring humus into the soil, which feeds that mildly “parasitic” aspect of plant growth. In Alan Chadwick’s terms, there is a moment when a plant becomes more—it becomes a conservatoire, providing more than it takes to the soil.

Who is this moment? It is not Lucifer because Lucifer is the discharge of energies from the soil back to the cosmos. It is not Mephistopheles because this is the pure accumulation of potential energy. The influx of new light and life is the Christ impulse. As an esoteric maxim goes, Christus Verus Luciferus. Christ is the true light-bringer.

The carnivorous root craves darkness and shuns light, and the twilight of the leaf draws on both light and darkness. The flower itself surrenders to the light, offering the possibility of a new incarnation to future life. As Steiner indicates in one of his medical lectures, roots hunger after the sunlight of "the year before" in the form of humus and salts, whereas the leaves are of a mixed quality:

“The plant in growing from the soil in its year is at first really growing with the powers which the sun has given to the earth the year before if not earlier, for the plant takes its dynamics from the soil. These dynamics taken from the soil can be traced as far as the ovary, as far as seed development. We therefore only have a genuine botany that is in accord with the whole physiology if we take account not only the dynamics of warmth and light and of light conditions in the year when the plant is growing, but starting from the root base ourselves on the dynamics of light and warmth at least in the year before. We can trace this as far as the ovary, so that we have something in the ovary which happened the year before still active from the year before. If on the other hand you study the foliage, and even more the sepals and petals, you will in the leaves find a compromise, I'd say, between the dynamics of the year before and the dynamics of the current year. The leaves have in them the element pushing up from the soil and the influences of the environment. In petals the current year finally shows itself in its purest form. The colours and so on in the petals are not something old—they are of this year.”30

Image by Stewart Lundy. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission.

Image: In the roots, you have the working of last year (2022 - blue), in the leaves, you have a compromise (2022 and 2023 - green), and in the flower, you have the current year (2023 - yellow).

One might even call humus the sunlight of yesteryear, as it is more than half carbohydrates, which are a form of stored sunlight from previous seasons. But it is in the flower that “the current year finally shows itself in its purest form.”31 As Steiner puts it, “in the development of the plant from below upwards, in the production of the leaves and blossoms, we have, fundamentally speaking, a process of devitalisation.”32 As the plant grows under the sun’s influence, it discharges the vitality in the soil and becomes progressively “devitalized.” On the one hand, the flower is the full surrender of the plant to the oneness of the cosmos, but the flower is also the most refined expression of desire for differentiation as a new seed. The chthonic root wishes to grasp every vestige of the past with its tendrils, the green leaf to discharge what it has wrested from the root in its abstract love for the light, but in the flower and its seed, we see the particularized openness to the next generation of life even at the expense of the mother plant’s own life. It is not enough to love wisdom in abstraction, nor to love oneself, but rather to propagate love. Steiner says, “To disseminate love over the earth in the greatest measure possible, to promote love on the earth — that and that alone is wisdom.”33

As it is written, “Your darkness shall be changed into clear light.”34

Rudolf Steiner, Physiology and Healing, pp. 85-86 CW314.

Lewis Hyde, The Gift

The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Vol 1, Translator’s Introduction

Exodus 33:20

T.S. Eliot, Burnt Norton, Four Quartets

As Rabbi Tzvi Freeman says, quoting the Zohar: one is short, one is long, and one is intermediary (even though it is longest). In the tree of sephorith, these are the three pillars. This is to say: one is contractive (“short”) and one is expansive (“long”), and one that reconciles the two (“intermediary”) which emerges superior to either extreme, though. The plant that richest its fullest potential denies neither extreme, but is also not tepid compromise.

Anonymous, Meditations on the Tarot: Journeys into Christian Hermeticism, pg. 239

Commentary to Liber de causis 1,6

Goethe, Metamorphosis of Plants

Steiner, Rudolf, Stuttgart, February 8, 1909, GA98

Steiner speaks of "etheric oils" in his notes to the Agriculture Course. See: Creeger-Gardner translation.

Steiner, Rudolf, Agriculture Course, 12 June 1924, Koberwitz

Steiner, Rudolf, Nutrition and Health, Lecture I (GA354, 31 July 1924, Dornach)

R. Steiner, Man as Symphony of the Creative Word, Lecture XI, GA230 (10 November 1923, Dornach)

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture V, GA327 (13 June 1924, Koberwitz)

The Complete Works of Meister Eckhart, Sermon Eighty-Three, pg. 450.

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture II (GA327, 10 June 1924, Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Lucifer and Ahriman (GA191, 15 November 1919, Dornach)

See: Steve Solomon, The Intelligent Gardener

R. Steiner, Gospel of St. John, Lecture XIV (GA112 July 1909, Cassel)

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture IV, (GA327 12 June 1924, Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Supersensible Knowledge (GA55, 22 November 1906, Berlin)

Hans Urs von Balthasar, Heart of the World

R. Steiner, Goethe’s Standard of the Soul (GA22)

Goethe, Faust

R. Steiner, On Chaos and Cosmos, (GA284, 19 October 1907, Berlin)

Sir Albert Howard, An Agricultural Testament, Chapter 2

“For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” Matthew 18:20

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, (GA327, 12 June 1924, Koberwitz)

Rudolf Steiner, Physiology and Healing, pp. 85-86 CW314.

R. Steiner, Physiology and Healing, GA314, 89.

R. Steiner, The Anthroposophical Approach to Medicine, Lecture IV, (GA314 Stuttgart, 28 October, 1922)

R. Steiner, Love and Its Meaning in the World (GA143 17 December 1912, Zurich)

Isaiah 58:10

this is extraordinary! thank you, Stewart. I feel I am in the presence of a wise man, reading this, and I am grateful for the vision that you share.

Relistened to this today and feeling all of the Love you share Stewart 🙌🏼 thank you for this gift and shining Light into this world ❤️❤️❤️✨✨✨