Parallel Streams

Alan Chadwick's Dynamic Agriculture

“It’s a Chadwick garden…”

Before sitting down to write this article, I knew relatively little about Alan Chadwick and the gardening methods he pioneered. Now I’m devising ways to make my own U-Bar and rethinking all of my garden bed plans.

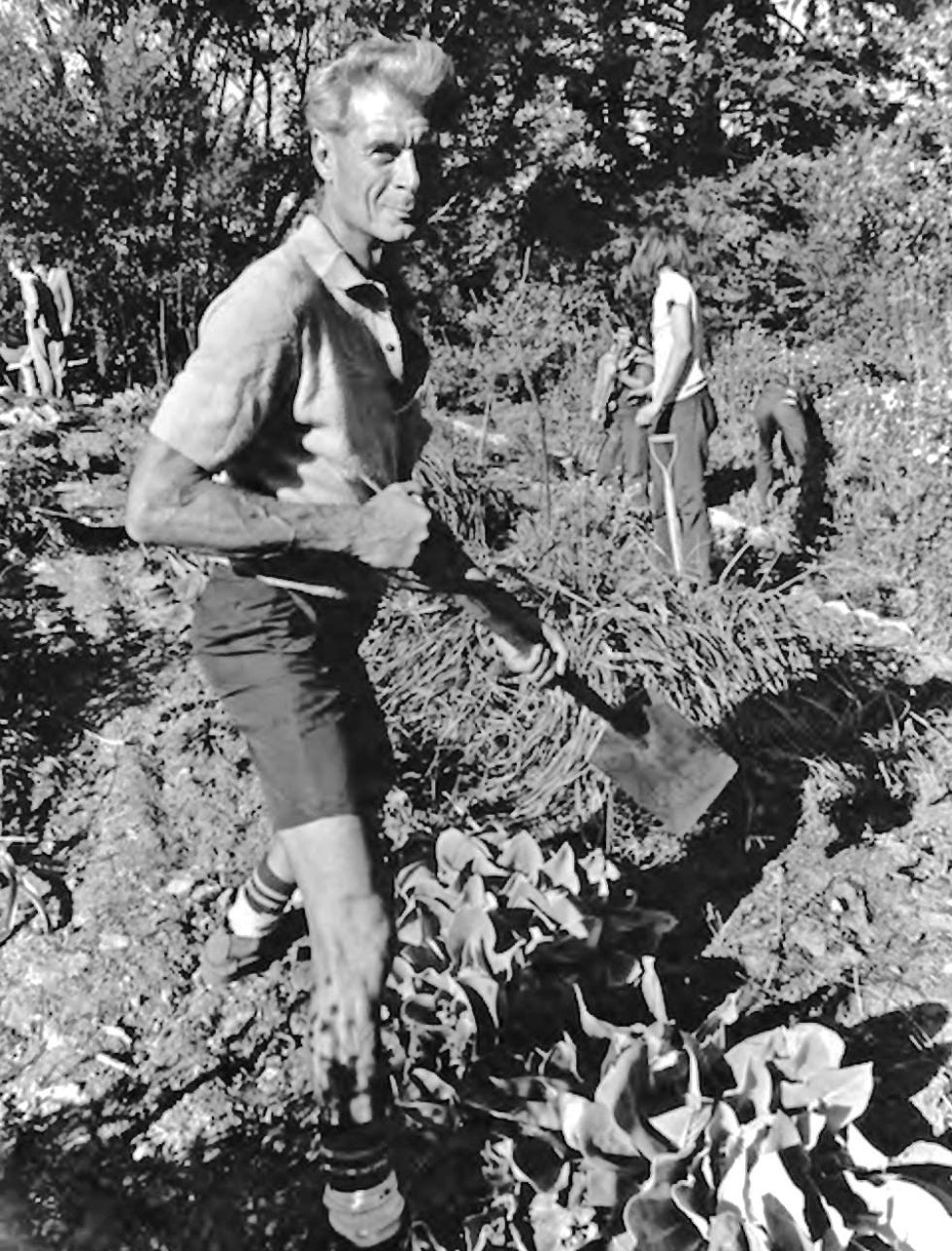

Alan Chadwick was an anthroposophist, thespian and master horticulturist who lived from 1909 to 1980. He created a technique called the “Biodynamic French Intensive Method” and is credited with sparking the organic farming movement in North America – but when people talk about his method, or when they’re standing in a garden where his techniques are being used, they usually just say, “it’s a Chadwick garden.”

I’ve learned “a Chadwick garden” is a lot simpler than you might think.

What gives “a Chadwick garden” its name? Double dug long furrows of organic raised beds, deeply pierced with a fork or u-bar, shaped with care and layered with bone meal and homemade compost, then densely planted with vegetable, flower, grain or cover crop, in rotation.

That is the gist, in the simplest of terms, but there is so much more beauty to a Chadwick garden than that. There is so much story and soul in the legacy of Alan Chadwick.

Alan Chadwick came from real British money. Aristocracy. His boyhood was spent in the grand backyards of the finest estates and his aristocratic mother, Elizabeth Alcock Chadwick, was by all accounts elegant, refined, artistic and happy. Elizabeth was thirty-three when Alan was born, and instilled her love of nature and gardens. She was an early member of the Anthroposophical Society in Britain, and knew Rudolf Steiner personally.

As a youth and young man, Alan was tutored by many in his mother’s circle, including Steiner. Later in life, Alan would say that he was a “child of Steiner” and that Steiner was “the one tutor who had the deepest lasting influence” on him.1

Alan loved the theatre but was forced to study “something real”. So, he studied horticulture and attended some of the finest schools in Europe.

He disclaimed his inheritance and spent years trying to make it as an actor. Eventually, Alan embraced horticulture as a soul purpose and committed himself to the craft and to sharing his knowledge and skills.

In his own words, Alan explained, “Horticulture has always and is always and will always be craft, a great craft, the greatest of all of the arts. The art of the creation of God.”2

Alan’s aim was always to direct people back to the plants and the soil itself. He lamented what he called “compaction”, the destruction of aeration in the soil which meant the destruction of drainage. Drainage, he explained, was essential for the soil to breathe in the changing atmosphere, “for the operation of the Stars and the planets of the cosmic world [that] operates in the soil as well as in the air.”3 A soil that is collapsed and compacted cannot breathe and thus cannot inhale the subtle streams from the cosmos.

He said, “It is high time to realize that in the whole of horticulture and agriculture, the atmosphere is as or more important than the soil and that the atmosphere is never the same one day as another, and that in the fall it is almost opposite in its formations as it is in the spring, and likewise with the soil, everybody thinks that soil is dirt, it’s there forever; you can tread on it, jump on it, bite it, eat it, kick it, throw stones on it, do anything you like on it, and it is it the same in the fall as it is in the spring, and the same in the winter as it is in the summer…completely untrue. The soil of spring is the very opposite to what is soil in the fall.”4

What emerges in spring is what is moving back into the earth in autumn. In spring, the earth is teased by the approaching summer sun to release moisture. In autumn, the lengthening nights give cool moisture back to the earth. Any gardener who has worked with soil in the spring and autumn can feel the difference. When we add the work of spraying biodynamic preparations, the purpose becomes clear: we are working with and enhancing celestial atmospheric qualities already present in the air, soil and plants.

Chadwick’s French intensive method evolved from an old set of French techniques originally created in the 1890s to achieve the highest possible productivity and quality of produce for market sale. Using planting designs with precise, tight, non-row spacings, interplanting, and clever companion planting mimics nature’s genius and inherent sustainability.5 The fluffy perfect mounds are glorious, with crops planted so densely together, they create their own canopy and block out weeds while maintaining moisture. Deeply forking the ground while double digging ensures drainage and air, allowing microbes space to nourish and flow. With the thump of the shovel and rhythmic swipe of the hoe and the rake, the gardener joins in nature’s chorus.

Here is the link to an incredible online archive of Alan’s work that includes videos of his speaking presentations, biographical information, techniques and testimony where one can lose oneself for hours (believe me). There are also wonderful films about the garden Alan built with students at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC).

“Garden” (1971) by Michael Stusser is a 16mm film featuring poetry and Alan’s words, set to stunning images of Alan’s garden and capturing the students’ work in gorgeous Californian sun.

“Garden Song” (1980) is a documentary that tells more of the history and context of the garden initiative at UCSC, produced by Bullfrog Films. Taking place at the height of the Vietnam War, the film depicts a time not dissimilar to the time we are experiencing now, when many young people were wanting to get back to the land and learn how to grow food.

I was surprised to find how incredibly complimentary French intensive methods can be with permaculture principles. One of my favourite permaculture farmers, Michael Hoag successfully incorporated French intensive methods into his permaculture garden, and wrote:

“For me, my gardening, and my understanding of Permaculture, which is about using DESIGN to achieve a goal, there has been nothing more important than understanding how to control levels of “intensivity” in the landscape. This is as true for the home garden, landscape, or homestead as it is for the profitable farm. By levels of “intensivity,” we’re talking about a spectrum where we let nature do all the work on one side, and on the other side, we add “inputs” like energy, work, time, water, fertilizer, pest-control and most importantly planning and design. And when it comes to this one point, I have learned a great deal from French Intensive Gardening, and the simplified systems taught by Alan Chadwick (Bio-Intensive French Gardening) and John Jeavons (Grow Bio-Intensive.)”6

John Jeavons is often mentioned alongside Chadwick. For the last forty-three years, Jeavons has been bringing sustainable mini-farming techniques inspired by Chadwick’s French Intensive Method to communities around the world. His “Grow Bio-Intensive” methods are currently being used in 143 countries in virtually all climates and soils where food is grown.7 Chadwick liked to say technique, technique, technique until the technique becomes invisible — Jeavons’ approach is just that. On only 2000 sq ft you can grow a complete diet for one person year round and he's got the numbers to prove it, too.

Alan Chadwick created gardens of sublime beauty and productivity by putting the consciousness of nature front and center, and by not being afraid to get his hands dirty.

For How-To videos of Biodynamic French Intensive Techniques, click here.

Alan Chadwick Archive Early Life Biography https://chadwickarchive.org/early-life-biography/

From “Garden Song” Interview #1 of 8, The Alan Chadwick Living & Archive www.chadwickarchive.org

From “Garden Song” Interview #1 of 8, The Alan Chadwick Living & Archive www.chadwickarchive.org

From “Garden Song” Interview #1 of 8, The Alan Chadwick Living & Archive www.chadwickarchive.org

Michael Hoag, French Intensive Methods for Permaculture, 2018 https://transformativeadventures.org/2018/05/15/french-intensive-methods-for-permaculture/

Michael Hoag, French Intensive Methods for Permaculture, 2018 https://transformativeadventures.org/2018/05/15/french-intensive-methods-for-permaculture/

John Jeavons https://johnjeavons.org/

I really needed to see this today.

Thank you.

The beauty of the flowers singing their song and the vibrancy of the vegetables and gentleness of the people tending their lives on the land.

Hope, in this crazy world.

I believe that the Garden was at University of Santa Cruz, rather than University of California, Berkeley.