Developing a newly received idea is a bit like trying to create a stabilized new variety of tomato. Your initial cross with some other heirloom variety makes a first-generation cross (“F1”), which may have some wild variations from plant to plant. But if you carefully save seeds from those that remain “true to type” and plant them again, you get the next generation F2, which still has some surprising variations. But as you proceed to F3, F4, F5, etc., you eventually get to a stabilized variety that produces a particular kind of new tomato consistently. In the world of ideas, we must likewise “interrogate every spirit” and let them grow repeatedly within us. If our idea is a strange hybrid between incompatible species, it will soon prove itself: the idea will stop being able to reproduce, or it will regress back into some wild, thorny thing.

What I experience as epiphanic flashes of insight arrive like little visitors. If I do not quickly write them down, they often vanish, leaving no trace but a vague residual feeling. But even if I write down thoughts (and I have entire journals full of them), sometimes I return to them and experience a dazzling few sentences but without enough of their context to understand what had been so clear before. The significant thing is that the feeling of otherness to my thoughts is not lost with time, but rather, the recognition of these sentences as ideas that do not belong to me only becomes intensified as they are further investigated.

An idea arrives, grows, and blossoms. Sometimes, this takes years because not every idea is a rapid-growing annual crop. Some ideas are like biennal blackberries. Other ideas are like perennial shrubs. Still others, germinating in secret under the thicket of rivalrous ideas, are veritable sequoias. But the “big” ideas don’t start looking big, and they often grow the slowest of all. By the time you notice something like a cedar of Lebanon rising above the tangled mess of your everyday thoughts, it is well on its way to transforming the entire landscape and, eventually, crowding out the very area formerly occupied by smaller, thornier plants.

Some people have a slower inner cycle — some a faster one — in which seeds germinate, grow, and blossom at various rates. This depends enormously on the individual and what kind of inner garden they tend. But before sharing ideas that germinate, they should be allowed to go dormant in us — and germinate again. And go dormant again and germinate once more. Seed-saving isn’t just something to do in the garden, it’s something to practice within your own soul.

One intuitive “flash” that arrived to me concerns the nature of making the biodynamic chamomile preparation (503). It struck me that Steiner’s indications were given to the rural Koberwitz estate and that he gave relatively simple instructions: “Instead of using these intestinal tubes as they are commonly used for making sausages, make them into another kind of sausage—fill them with the stuffing which you thus prepare from the camomile flower.”1 This is as simple as it gets. But what struck me was that anyone who already knew how to make sausages would have naturally and instinctively — without needing to be told by Steiner — turned the sausage casings inside out according to well-established traditions. No one would even have thought to leave the “dirty” side on the inside.

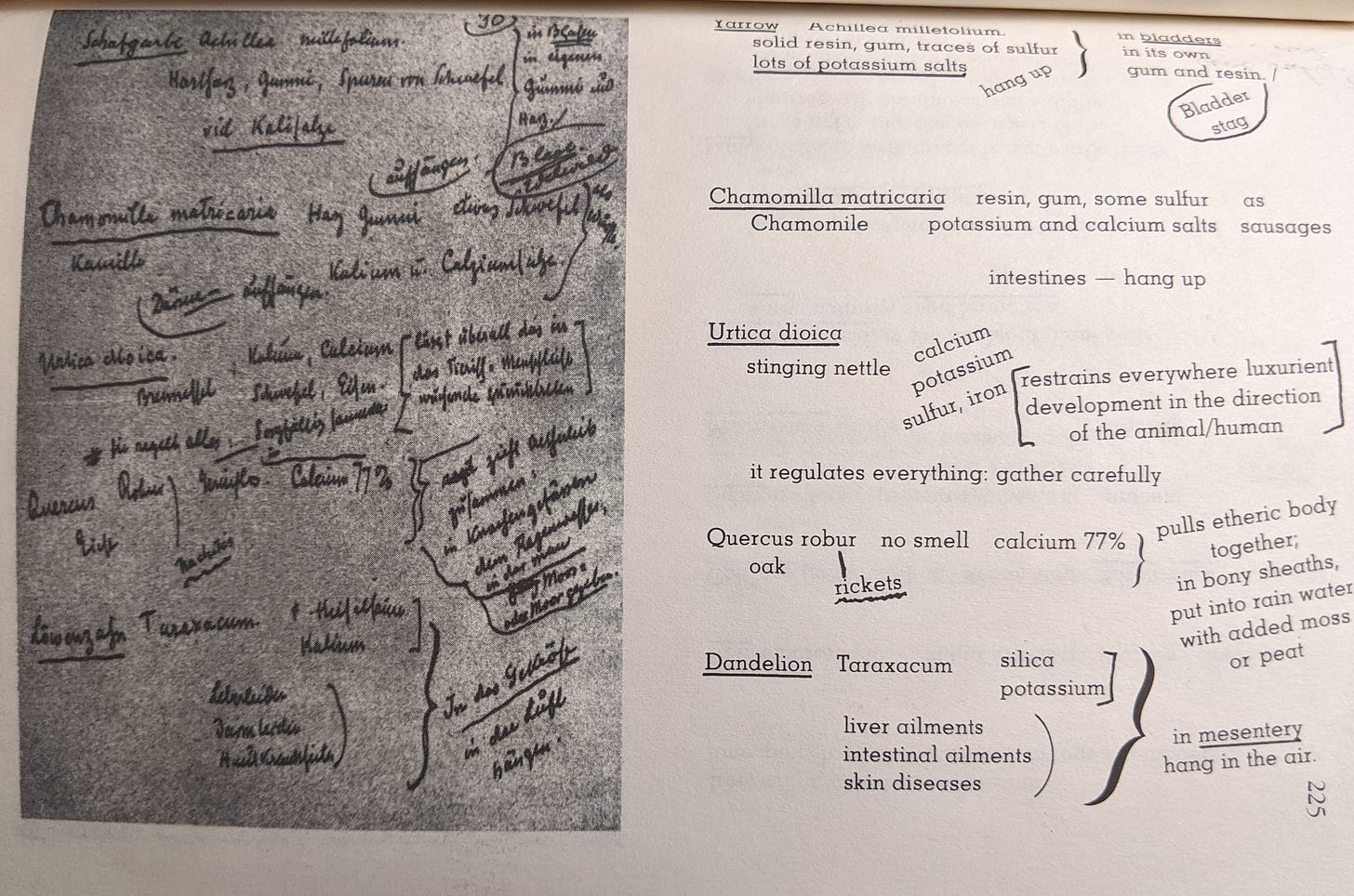

In Steiner’s handwritten notes at the back of the Creeger-Gardner translation, he clearly indicates that not only is the yarrow preparation to be hanged over summer, but he also includes the chamomile and dandelion preparations. I trust Steiner’s own notes more than someone else’s notes at his lecture because you know for a fact these were Steiner’s own thoughts without the mediation of someone else’s interpretive lens.

In my research, I found that Alex Podolinsky himself tried hanging the chamomile sausages according to Steiner’s instructions but found that the fat went rancid and quickly discontinued the practice. Notably, Podolinsky did not try inverting the sausages to the best of my knowledge. When normal sausages are made — according to true peasant wisdom — the extra animal fat finds its way into the inside of the sausage, where it is prevented from going rancid. After all, Steiner said that it had been his destiny to write a book of peasant wisdom — a destiny that he set aside to edit Goethe’s natural scientific work. And yet, perhaps precisely because he suppressed his own “destiny” biodynamics emerged as a sort of swansong that is still developing today. Though biodynamics itself is not exactly a codification of peasant wisdom, it remains close to Steiner’s destiny even when the rest of us have perhaps forgotten the peasant art of sausage-making.

Podolinsky goes so far as to suggest that Steiner’s indications about hanging the sausages may have been misguided because they weren’t made from practical, experiential knowledge. My late mentor, Hugh J. Courtney, would carefully cut away any external fat from the intestines when making the sausages, leaving the “messy” part of the intestines on the inside, which is standard procedure worldwide as far as I can tell. By carefully removing all the fat, fewer vermin are attracted. This much is true. But if the fat is on the inside, the precious animal fat is contained and does not go rancid.

The Paracelsian alchemist and father of agricultural chemistry, Wallerius2, writes that the purpose of manuring is “fattening” the soil. Rudolf Steiner says something analogous when he says manuring is “enlivening” the soil. When we consider that Steiner’s handwritten notes for the Agriculture Course speak of “etheric oils” the image becomes much clearer.

In all this, I had a strongly felt idea, so I went about trying it. I ran anecdotal experiments on my own. I inverted the intestines from one of our cows, stuffed the clean insides with chamomile grown on our farm, and hanged them over spring and summer, where they would receive light all morning but be shaded from the desiccating late afternoon sun. What I discovered is that not only did these turn out well, but the animal fat melded beautifully with the flowers: the alchemical sulfur pole of the animal united with the sulfur pole from the plant.

Only after having experimented with this myself did I find the following passage from Dr. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer in some of JPI’s proprietary documents, which I would like to share with you today. This, to my knowledge, has never been published in any form before:

“Get cattle intestines , the so called small intestines or duodenum before the ileum. Clean the intestines with cold water and turn inside out and blow up to keep dry until use. You may also fill the intestines with straw to avoid glueing together. When you have all the blossom together, fill the intestines making sausages and tie the ends with a string.” 3

Consider how all the assimilation processes in our food are really a kind of breathing. We break down our food into its various aromatic compounds — we make it stink — and those forces radiate into our being. Paracelsus himself suggests that the power of manure is in its odor, and that is what we seek in our food. The bulk of the physical weight of our food leaves our bodies, but we assimilate the forces that radiate when we break it down by means of digestion.

“Taken as a whole, life itself consists in this that what is generally diffused as a scent is instead held together so that the scent is kept inside and does not stream outwards too strongly. An organism must therefore allow as little as possible of its scent-producing life to escape outwards through its skin. Indeed, one might say that the healthier an organism, the more it will smell inwardly and the less it will smell outwardly. A living organism and particularly the plant organism (apart from the flower) is designed not to give out scent but to take it in.”4

Because the intestines are semipermeable membranes, especially energetically and especially to scents, why would we imagine that the “Ahrimanic” destructive process of bacilli is what we’re trying to preserve in the biodynamic preparations? Alex Podolinsky was right when he championed the biodynamic preparations not as forces of decomposition but as etheric formative forces: forces of construction, not destruction.

If the biodynamic preparations are life forces, not the forces of death and decomposition, then shouldn’t we want to invert the sheath? By inverting the sheath, we place the “hungry” side on the outside, and as it ripens in the sun, it “eats” the environment and assimilates more of the cosmic forces within the preparation.5 Thus, I invert my intestines so they aren’t “eating” my precious chamomile at all but, conversely, absorbing scent from the cosmos itself. When sausages are hanged with the green chime on the inside, the forces of destruction have a tendency to predominate and radiate scent — just as they are designed to do within a cow. But outside of a cow, there is nowhere to radiate the chamomile scent but out and away into the cosmos.

Unearthing chamomile preparation (503) with Adam Orlando.

After all, “If possible, choose a spot where the snow will remain for a long time and where the sun will shine upon the snow, for you will thus contrive to let the cosmic astral influences work down into the soil where your precious little sausages are buried.”6 If we wish to absorb the fullness of such “cosmic astral influences” then, I suggest, we may want to have the “hungry” aspect of the intestines facing outward. It’s a minor change, but I challenge you to give it a try.

Fortunately, Nature is quite forgiving. If she weren’t, then we would all be in big trouble. I have no reason to doubt the effectiveness of the biodynamic preparations I made before inverting them — or that of anyone else. But there is something precious about these sausages, and I want the full intensity of the forces intended when these were initially formulated. If this can prove stimulating and help some other souls to revisit what Steiner shared with new curiosity, then the work has been done. Thank you for being with me on this journey — and let me know what you find out in your own experiments!

Upside Down Biodynamics

“[T]he fragrant flowers of a large number of plants are really organs of smell; they’re vegetable organs of smell which are extraordinarily sensitive. And what do they smell? They smell the omnipresent world’s aroma.” - R. Steiner

What We’re Reading

The Agriculture Course by Rudolf Steiner. 2024 is the 100th year anniversary of biodynamics, and we’re co-hosting a study group exploring this special text with Spikenard Honeybee Sanctuary. Be sure to get a copy! If you want to read Steiner’s handwritten notes, be sure to get the Creeger-Gardner translation.

What’s New?

A lovely interview with Sharon Carson from Delmar, Delaware. A lot of people have crossed Sharon’s path. There are almost no biodynamic practitioners near me (Stewart) but Sharon is one special holdout against industrial agriculture. Other biodynamic notables such as Mattias Baker made their way through Sharon’s place back in the day. I met Sharon quite a few years ago — many of the plants and seeds carried with myself and

at Perennial Roots Farm. Please check out this interview and share it with your friends!I myself was also interviewed for Heart & Soil Magazine about the book I put together, published through SteinerBooks, Biodynamics for Beginners by Hugh J. Courtney. This book is a compilation of some of Hugh’s favorite articles from Applied Biodynamics during its print iteration. Get a copy now!

What we’re using in the garden

This time of year, if you’re having as much rain as we are, it’s time to break out horn silica (501) and Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) to improve photosynthesis, biotic and abiotic stress resistance, and help combat fungus and mildew pressure. When it comes time for crop rotations, I always use Barrel Compound (BC) to spray as I turn under or transplant new crops. Using Barrel Compound through the season helps guarantee that the vitality in garden beds never fully die out and keeps everything operating within the realm of the living.

Equisetum and Fungus: Good and Bad

In a prehistoric epoch, the earth was too hot for water to condense into rivers, lakes, or oceans. Instead, other compounds like silicon were fluid. We might say molten but the entire earth did not yet have a solid crust. The earth was once too hot for water to condense into rivers, lakes, or oceans. As Steiner says, “As long as the earth was soft, such…

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture IV (GA327, 13 June, 1924 Koberwitz)

Translated across several languages, in the process of which the origihttps://drive.google.com/file/d/1YCX3gI11PV3PeV5Guj2P1YEF8Uqi6Ux_/view?usp=sharing

BD Compost Starter notes by Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, JPI Archives

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture IV (GA327, 12 June 1924, Koberwitz)

Whether the sheath is inside or or not still technically follows the letter of Steiner’s indications. Steiner did not say to invert the intestines (or not), but common sense should prevail.

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture V (GA327, 13 June, 1924 Koberwitz)