Under the Microscope

Biodynamics & Microbiological Diversity

“We need to create the beauty and the quality first. The quantity will follow.” - Alan Chadwick

Ask yourself: is a compost pile alive because it has microbes, OR does a compost pile have microbes because it is alive? In biological farming, one might say that the compost pile is alive because of the abundance of microbial life to be found in it. In biodynamics, the focus is shifted slightly to emphasize that microbes only appear because there is appropriate food — forces — required for their existence.

In biodynamic circles, there is a strong emphasis on quality in the face of an overwhelming societal influence towards quantity. But just because quantity is overemphasized does not mean that quantity is unimportant. We need both quality and quantity. However, having good quality food — even if not enough of it — is arguably better than having too much poor quality food and all the attendant dietary diseases that arise.

Yes, we need vital food rich with nutrients and forces necessary to thrive — and we need a lot of it. If we have poor quality, it doesn’t matter how much of it we have; more bad food does not make up for a lack of nutrition. This is the problem with so-called “food deserts,” where entire populations are severed from having decent food. No amount of eating more bad food can offer health. We often need to eat far less but of much better quality. That this isn’t readily available to everyone is an injustice, and one biodynamics cannot even begin to claim to remedy. But we can work where we can as we are able and generate nutrient-dense food where we can as we can. When Ehrenfried Pfeiffer asked about the lack of spiritual development, Steiner told him it was a “problem of nutrition.”1 When the human organism is fed impoverished food, this weakens the ability to turn ideas into practical action.

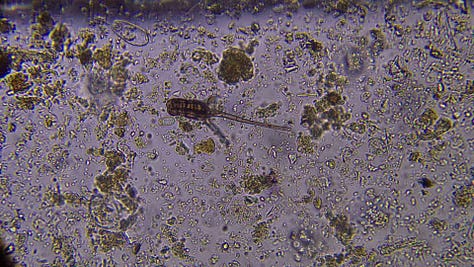

Barrel Compound under microscope: bacterial feeding nematode with two amoeba attached.

As Steiner says, “One must work in a businesslike, profit-making way, or it won’t come off.”2 At the end of the day, a farmer must be able to earn a living. Idealism without practicality is not the path Steiner championed. What he did propose, though, was the farm as an “organism” that strives — as much as is practical — to generate fertility from within its own circle. What has been called “indigenous microorganisms” (IMOs) are active in the biodynamic preparations, especially when made in your particular bioregion. But what happens if you are in an area that has undergone desertification due to human abuses? The microbiological diversity is gone from many soils because there is no food for those microbes.

This is where biodynamics takes an ontological step behind biological farming. We love to see healthy diversity in soil and applaud the M.A.D. principle (maximum abundance & diversity) in soil health. But Steiner cautions us that merely adding microbes isn’t enough. Why? Because microbes need food.

At one point in the Agriculture Course, Steiner paints a picture describing a “dirty” kitchen in which there is food left out and flies show up and continue to reproduce: “A large number of flies are found in a room and because of this the room is considered dirty. But the truth is that the flies are there because the room is dirty.”3 While flies may stray into a clean kitchen, they won’t be able to reproduce without food. But if a messy kitchen, with food scraps lying about, is left that way, flies can not only show up but can reproduce in abundance. This is the exact same principle applying to both desirable and undesirable microbes in our soil: they all require specific conditions and food — forces — to sustain them.

As such, biodynamics is not merely about adding the good microbes but doing what numerous soil web advocates are already doing: providing the right habitat and sustenance for microbiological diversity. The biodynamic preparations, as Alex Podolinsky strongly argued, are not forces of decomposition — but rather “etheric formative forces” — the power to build up new life. When we make biodynamic preparations out of medicinal herbs and animal parts, these are suitable substrates for distinct varieties (and sufficient diversity) of emergent microbiological life. But bacteria and fungi feed on the potential energy stored in food and are a symptom of having the right forces available.

Bacteria and fungi feed on the potential energy stored in food and are a symptom of having the right forces available.

It is as if the biodynamic preparations are like a kind of prebiotic, which provides suitable food for probiotics (beneficial microbes), which spontaneously arrive in a healthy ecosystem. But if an ecosystem has become impoverished, microbiological diversity needs to be imported. This is done with medicinal applications of biodynamic preparations or even soil from a fertile field in our bioregion. Under a microscope, we can see the microbes, but we cannot see the “forces” upon which microbes feed.

This is why Steiner says that it’s not enough merely to apply microbes: “If we think that by inoculating the manure with these bacteria we shall radically improve its quality, we are making a complete mistake. Externally there may seem at first to be an improvement, but in reality, there is none.”4 Instead, we must also provide the right qualities — the right forces — that can continue to sustain the kinds of symptomatic soil biology we desire.

Consider another example: if you moved sheep to a barren patch of land with no grass and also gave them no food, their “regenerative” powers would be completely useless. Animals moved to a dead field must be supplemented until the field is enlivened enough that it can sustain its own vitality. The same goes for soil microbes. Mycorrhizal fungi don’t mean much if there are no plants for them to get their source of sugars — energy from the sun. All lifeforms require food to sustain their existence. Our job is to provide the forces contained within appropriate “foods.”

Steiner describes plants as “mildly parasitic” — in the sense that they consume forces within humus. Likewise, plants rely on a steady in-streaming of energy from the cosmos. Bacteria too. But what does a microscope offer us? It offers a clue that a particular manure sample is in a particular state or in another. The end-all-be-all of biodynamics is not microscopy, but what can be witnessed under a microscope tells us clearly that manure has undergone a healthy transformation — or not. Steiner says:

“What does science do nowadays? It takes a little plate and lays a preparation on it, carefully separates it off and peers into it, shutting off an every side whatever might be working into it. We call it a ‘microscope.’ It is the very opposite of what we should do to gain a relationship to the wide spaces. No longer content to shut ourselves off in a room, we shut ourselves off in this microscope tube from all the glory of the world.”5

In anthroposophy and biodynamics, the aim is to step outside ourselves and reach out to the stars again and, from there, introduce remedies. This may seem far-fetched to some, but everything here on Earth came from the cosmos. In fact, plant life is a symptom of the inflowing energy from the stars just as much as bacteria in a compost pile is a symptom of the energy contained in the compost materials.

For Steiner, “Microscopical methods are more apt to lead away from a wholesome view of life and its disturbances, than to lead towards it. All the processes actually affecting us, in our health and sickness, can be much better studied on the macroscopic than on the microscopic scale. We must only seek out the opportunities for such a study in the world of the macrocosm.”6 What this means is that the smaller the pieces we study, the more difficult it is for us to reintegrate these fragments into a unified vision of the universe. The macroscopic imagination must be developed to integrate microscopic findings so that they lead toward a wholesome view of life.

The macroscopic imagination must be developed to integrate microscopic findings so that they lead toward a wholesome view of life.

Here is the key to the biodynamic view: “[humus] is at its best just at the point where it begins to dissolve through the workings of its own astral and etheric elements. It is then that…. the micro-organisms make their appearance. They find a good feeding-ground in which to develop.”7 In Steiner’s articulation, all life forms are mildly parasitic in this limited sense: plants require energy from the sun and in the soil, microbes require food they did not produce, but this is also true of human beings: we eat what we could not magically create all the time. We shouldn’t feel guilty about this, but we should approach the earth and growing food with great reverence. There is always an unspoken debt in eating the gracious gift of food, and the debt of reciprocity is gratitude to the source of that food and mutual graciousness to one another.

In biodynamics, we aim to provide “a good feeding-ground” for the right kind of biological diversity. We do so with plants and animals — and a healthy soil cannot exist without both. What microscopes can tell us is whether we are providing “a good feeding-ground” or not. We do not need to become reductionistic or limit ourselves to microbes, but we also do not need to shy away from demonstrating that, yes, the biodynamic preparations are a rich source of food for microbiological diversity. As Steiner says, “the active forces are not in what one meets with the microscopic eye but are rather within what streams in from the cosmos, from the constellations in the cosmos.”8 In a way, we are looking at the backside of a woven broach or tapestry when we look under a microscope, but we aren’t seeing the whole picture. Unifying meaning is not supplied by the microscope nor by any of our external senses. Conceptual meaning must be discovered by intuitive thinking. By itself, the senses perceive a disorganized kaleidoscopic display of stimuli, but the mind must organize and recognize the meaning of what it sees.9

Are microbes everything? Of course not. But a thermometer can tell you if you have a fever, even if it cannot cure it. Microbiological analysis can tell you accurately if you have an infection, but how to cure that remains in the imagination and skill of a physician.

For example, the planet Uranus was discovered not with a telescope but was nonetheless confirmed with a telescope. The planet Uranus was discovered through the realization that the orbits of other planets “bent” in a particular and consistent way that suggested that a large hidden planet must be there. The existence of Uranus was proven through mathematical calculations and demonstrated to the senses with a telescope. The forces and recognizing the pattern of their influence had already “proved” the existence of Uranus in the world of ideas, but the telescope provided sense-perceptible proof. That is what a microscope does for us in relation to the soil: it reveals sense-perceptible proof and quantitative evidence of what we already know must exist when the right forces are provided.

As long as we remember that microbes arise as a consequence of diverse qualities of nourishment (forces), whatever is glimpsed under a microscope does not need to contribute to a disintegration of a feeling for integrated wholeness but rather demonstrate external confirmation of the macrocosmic view offered from the spiritual context of biodynamics.

Microscopes and what we can learn from them are symptoms of ontologically prior formative activities “behind” the scenes, which a microscope in itself cannot see. But then again, even the human eye cannot understand what it senses by itself either — it requires a living brain to interpret what is being seen. In a sense, both the eye and microscopes present something “untrue” if and only if we do not reunify with living thought what appears divided. Only when we stop at superficial appearances — what is perceptible to the external senses — and believe that is the entire scope of meaning are we deluded by maya. As we split things apart, a greater effort must be made to reunify what we have disintegrated. When we are unable to reintegrate what we have shattered, madness ensues.

Nonetheless, the accuracy of a good microscope can demonstrate clearly that any given preparation is a truly abundant source of food for microbiological diversity. Profit isn’t the sole aim of farming, but if it doesn’t produce a surplus, it isn’t working. Likewise, microbes aren’t the sole aim of biodynamics, but if biodynamics can’t produce microbiological diversity, it also isn’t working.

Microbes aren’t the sole aim of biodynamics, but if biodynamics can’t produce microbiological diversity, it also isn’t working.

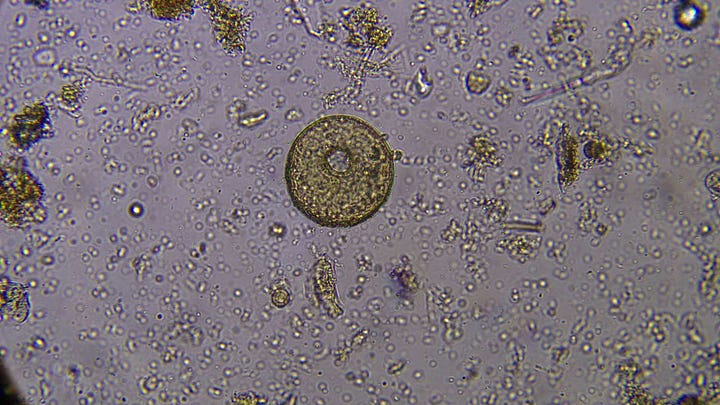

Our friends at Cure Soil visited with us at the 2023 Biodynamic Conference in Colorado, where JPI preparations were submitted to the gaze of their microscope. Not only were our preparations free from pathogens, but they showed a good diversity of microbial life. As indicators, diverse microbiological life demonstrates to the external eye the equally diverse food sources (“forces”) contained in these biodynamic preparations.

As long as we remember that microbes arise as a consequence of diverse qualities of nourishment (forces), whatever is glimpsed under a microscope does not need to contribute to a disintegration of a feeling for integrated wholeness but rather demonstrate external confirmation of the macrocosmic view offered from the spiritual context of biodynamics.

Cure Soil offers holistic soil testing services, from mineral reports, bio-assays, and genetic testing, to gain a comprehensive view of the current state of our client’s soils. From there, they provide specific management plans and custom applications of minerals and biology based on the data collected. Learn more.

R. Steiner, as quoted by E. Pfeiffer in the preface to the Agriculture Course

R. Steiner, as quoted by E. Pfeiffer in the preface to the Agriculture Course

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture V (GA327, 13 June, 1924 Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture IV (GA327, 12 June 1924, Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture VI, (GA327, 14 June, 1924, Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Spiritual Science and Medicine, (GA312, 24 March 1920, Dornach)

R. Steiner, Agriculture, Lecture VI, (GA327, 14 June 1924, Koberwitz)

R. Steiner, Reappearance of the Christ in the Etheric (25 November 1917, Dornarch)

See: R. Steiner, Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path.