In August of 2023, my wife and I purchased a parcel of land in the eastern highlands of Vermont’s green mountains. For two months, seven days a week, I worked with axes, hand saws, a chisel, and a mallet to build a small timber-framed cabin for our family by hand.

The project emerged from a combination of idealism and pragmatism. I long dreamed of building my own home, a seed first planted in my imagination when I read Walden as a teenager. I grew up in the artificial, disposable world of suburbia. So the idea of building my own dwelling by hand and, in the process, crafting my own destiny, was a clarion call. Homer’s Odyssey also had a strong effect on me, which may seem strange. However, the image of Odysseus and Penelope’s marriage bed, built around the trunk of a live olive tree as the center of the home he built with his own hands, worked its way into my consciousness. The idea of building my own dwelling became connected, for me, with the desire to enter deeper into life itself: to “not play at life,” as Thoreau puts it.

The project emerged from a combination of idealism and pragmatism.

In January of 2023, we spent six weeks in rural Transylvania, a region of Romania. The experience was a feast of vernacular architecture. All the houses in the village where we stayed were built by their owners — timber structures covered within and without by lime plaster and roofed with clay tiles. The homes seemed to belong to their place: the green and rose-colored plaster reflecting the fields of wild rose hips and balls of mistletoe hanging from the bare plum trees, the roofs reflecting the earth from which they were formed. It was in that context that we began to make practical plans to return to New England, purchase land, and begin building our own home. I wanted a home that, like the peasants’ cottages in Transylvania, would arise out of the land itself and reflect its individuality; which, when it was no longer inhabitable, could decompose back into the earth again without poisoning it. I signed up for a class on plaster and another on timber framing.

We started our land search in earnest in May 2023, but didn’t find anything until August. Through a family loan, we were able to purchase one hundred acres of land in central-eastern Vermont, about half an hour from the New Hampshire border. This is “marginal land,” once used for farming and grazing; but its history over the last century is punctuated by repeated clear-cutting for timber. The parcel is now wooded everywhere, in varying stages of succession, sloping in all directions towards a 15-acre wetland at the center.

Once we cemented the purchase in mid-August, I set to work figuring out how to get a structure up before winter. I was drawn to timber framing because of its strong local tradition, its economy, and its aesthetic values. After inquiring with several local sawmills about the timbers I would need, I found that no one could fulfill my order till late in November.

A timber frame preservationist who became interested in my project suggested that I hew the timbers myself, as was once common in New England. I agreed, as this would allow me to get started right away with minimal equipment. It would also allow me to source all the timbers myself from my own land. The cabin frame I intended to build would be an outgrowth of the land itself, reflecting the farm individuality in our dwelling as well as our garden, and would require little more than a few axes. The project would participate in Thoreau’s “economy,” saving us a few thousand dollars; and, in a romantic sense, awaken something asleep, with the sound of axes on wood as the incantation that would bring back an older spirit of building in conversation with the land.

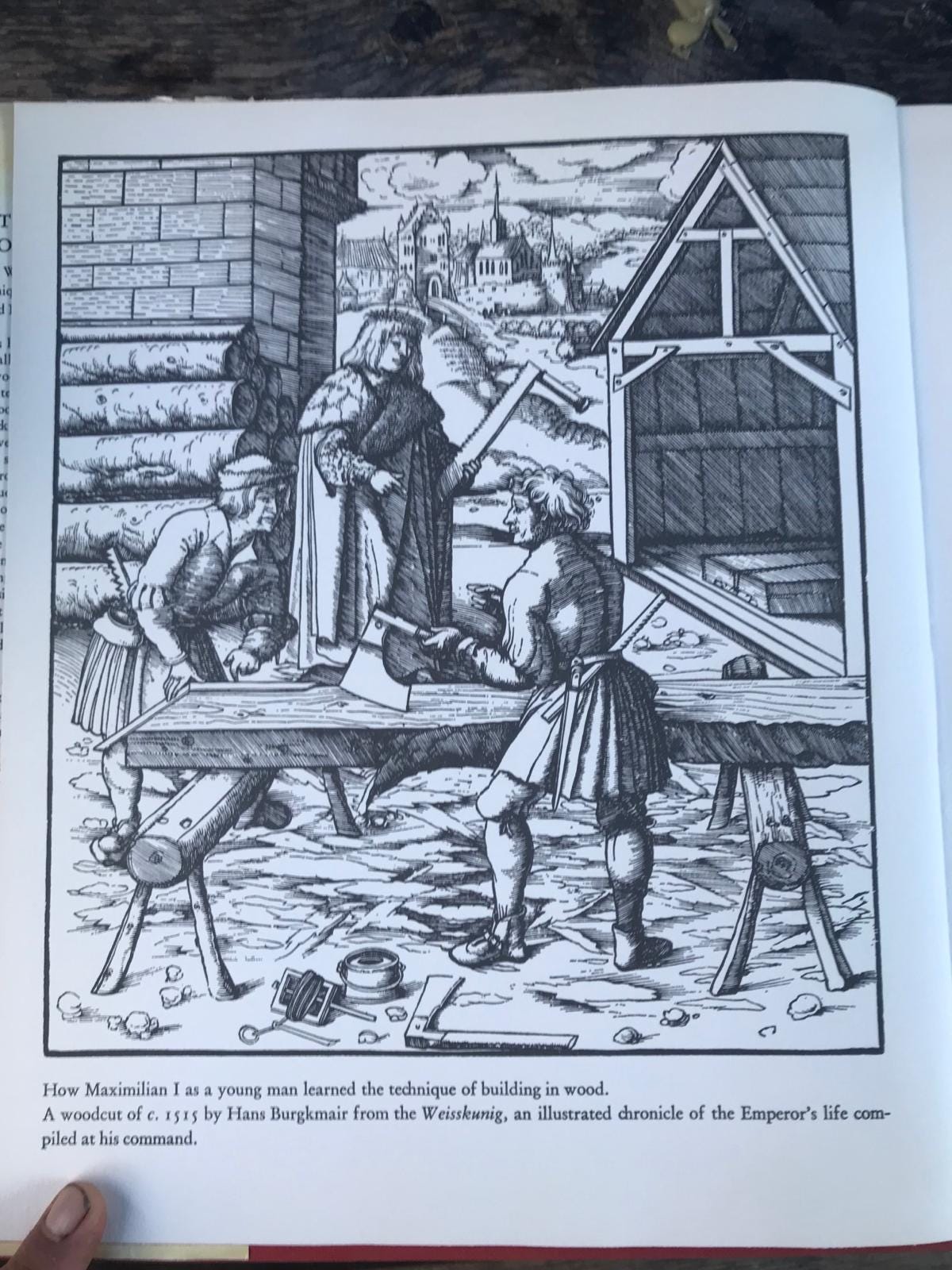

The very “primitive” nature of the project I undertook — to build a hand-hewn timber frame — was a large part of its attraction. I had been working for a tech company for four years, spending forty or more hours a week in front of a laptop, interacting with the world through a keyboard. I needed a strong detoxification program. The axe, one of the oldest human tools, became my medicine. This tool — its heft, its simplicity, its versatility — has a way of awakening very deep instincts in us, reminding us of our innate desire to make things, to shape the world. It seems almost as though our hands know the tool before our minds do! Of course, by the very fact that I chose this “slow” option among many possibilities, I thereby brought a new consciousness to my creative activity that would have been impossible for our ancestors.

My choice took on the nature of a rebellion against a lot of contemporary, tech-saturated culture. My methods and tools may have been old, but my reasons for using them were very contemporary. To put it in Jeremy Naydler’s terms, from his book The Future of the Ancient World, my project was an example of “being ancient in a modern way.”

Thoreau writes, “Before I had done I was more the friend than the foe of the pine tree, though I had cut down some of them, having become better acquainted with it.” This paradox was alive to me as well. The species that I used for my frame were black and red spruce, balsam fir, white pine, and poplar. I approached felling these trees and hewing beams from the logs with much trepidation, both for my own safety and for the precious life of the organism I was severing from its roots. Like Thoreau, however, by working with hand tools rather than power tools — an axe and crosscut logging saw instead of a sawmill — I feel that I did become better acquainted with my woodlands.

The slower, quieter nature of human-powered tools invites greater attention to what one’s hands are doing. The senses aren’t overwhelmed by the noise and smell of petroleum-powered tools. And while I cut the trees with some regret, I also knew that I was giving them a second life beyond slow decay on the forest floor.

The logging and building process I used is based on the traditional methods of New England timber framing. Common up until the mid-nineteenth century, they experienced a vigorous revival in the region beginning in the 1970s. I chose the trees based on the timbers I would need, looking for those that were straight and branch-free for the first twenty feet or so. I then cut them down with my felling axe, bucked the logs to length, and marked their edges with a chalk line to describe the planes I wished to cut. Then, working with a broad axe — a special type of axe with a thin edge designed for slicing — I squared the sides to the lines I had laid out. By the time this was done, I had removed about a third or even half the weight of the tree.

With the help of friends, I carried the beams out of the woods by hand. From there, what remained was cutting the joinery that holds the frame together. For this more precise work, I used a framing square and other measuring tools, as well as a chisel, mallet, and saw to cut the mortises and tenons for the joints. When everything was complete, we had a big gathering and raised the frame by hand.

I made some mistakes along the way but, in general, I feel that the project has been a success. As G.K. Chesterton says, “if something is worth doing well, it is worth doing badly.” Up until about a hundred years ago in Vermont, every farm boy knew how to hew a log and cut basic joinery for a barn frame. I probably did not even reach their level of skill, but I think I proved, to myself no less than to others, that what previous generations were able to do is still possible for an amateur like myself. Of course, I would not have been able to accomplish what I did without a lot of help along the way.

Much remains to be done. I envision the finished cabin as evoking a cottage in Scandinavia, a climate and culture very similar to ours in Vermont. The cabin will be enclosed with untreated wood siding, and painted with Swedish “falu red” paint, a traditional mixture of linseed oil and red oxide that both preserves and colors the wood while also allowing it to breathe. The window trim will be painted with white zinc paint, also Swedish. I am researching insulation now, and am considering mineral wool to resist moisture. The ideal I am working towards is a dwelling that can gracefully decay back into the elements of which it is composed without poisoning the earth on which it stands.

We envision this cabin as our outpost in a new territory, from which we will observe and begin to make plans for a larger homestead. When we took on this project, we already had some experience raising livestock and gardening on a rental property. We had Jersey milk cows, as well as pigs, chickens, ducks, and geese; we grew biodynamic produce with the help of a neighbor who lent us some of her well-tended garden beds. We certainly intend to go in this direction again, and will probably begin with pigs in the spring. Our land, overgrown and neglected, will require a lot of attention to bring it back into productivity.

When I first began acquiring livestock for our previous homestead, I read Rudolf Steiner’s Agriculture Course. The book is dense, and I do not claim to understand it all. The primary message I gleaned from it is the importance of the farmer’s conscious attention to the life of the farm organism. As he says in the Philosophy of Freedom, the world awaits our conscious thought; without it, the world is incomplete.

As Steiner says in the Philosophy of Freedom, the world awaits our conscious thought; without it, the world is incomplete.

Owen Barfield writes that Steiner is to our age what Aristotle was to his. Having read a lot of Aristotle as well as Steiner, I find this a very intriguing analogy. In his writings on almost every subject, Aristotle begins from the assumption that there is a rationality or teleology to human customs and practices, particularly very ancient ones, and his work is dedicated to uncovering this rationality.

Similarly, Steiner begins from the premise that myths, folk tales, traditional practices in agriculture and the trades, all have a latent rationality that’s up to us to uncover and articulate: hence, his attention to astronomical effects on earthly phenomena, as well as other variations on traditional practices that he recommended. In Owen Barfield’s terms, we ought to resist the attitude of “chronological snobbery” that is so prevalent in the intellectual atmosphere: the assumption that what is newer, is better. Tradition is a form of rationality; though it also contains much that is incidental, there is usually a core of deep insight at the root of traditional practices in all fields of endeavor.

I think a lot about the relation between the present and the past, and no doubt this preoccupation influenced my decision to build my cabin in a very traditional way. So much of modern culture is plagued by forgetfulness of what has gone before. In particular, when it comes to building, many people cannot even begin to contemplate using their own hands to build a dwelling for themselves, even if their ancestors of only a few generations ago could have done this with a few simple tools! If, in my simple and clumsy way, I showed that the past can still live in us, that we (even those of us who spend most of the day on a laptop) can recover some of the skills of our ancestors, then I am very happy.

So much of modern culture is plagued by forgetfulness of what has gone before.

John Carr cuts wood with an axe and scratches words onto paper with a pencil. Sometimes he opens a laptop as well to type out those words on his newsletter Homewords. Please subscribe to support his work on land and page. If you would like to directly support the cabin he is building by purchasing specific items needed to finish it, see the Cabin Gift Registry.

Beautiful. But you worked 7 days/week for over 3 months, not just 2... just sayin' <3

Very admirable and inspiring. Thanks.