New Interview: Introducing Biodynamics for Beginners

a conversation with Stewart Lundy

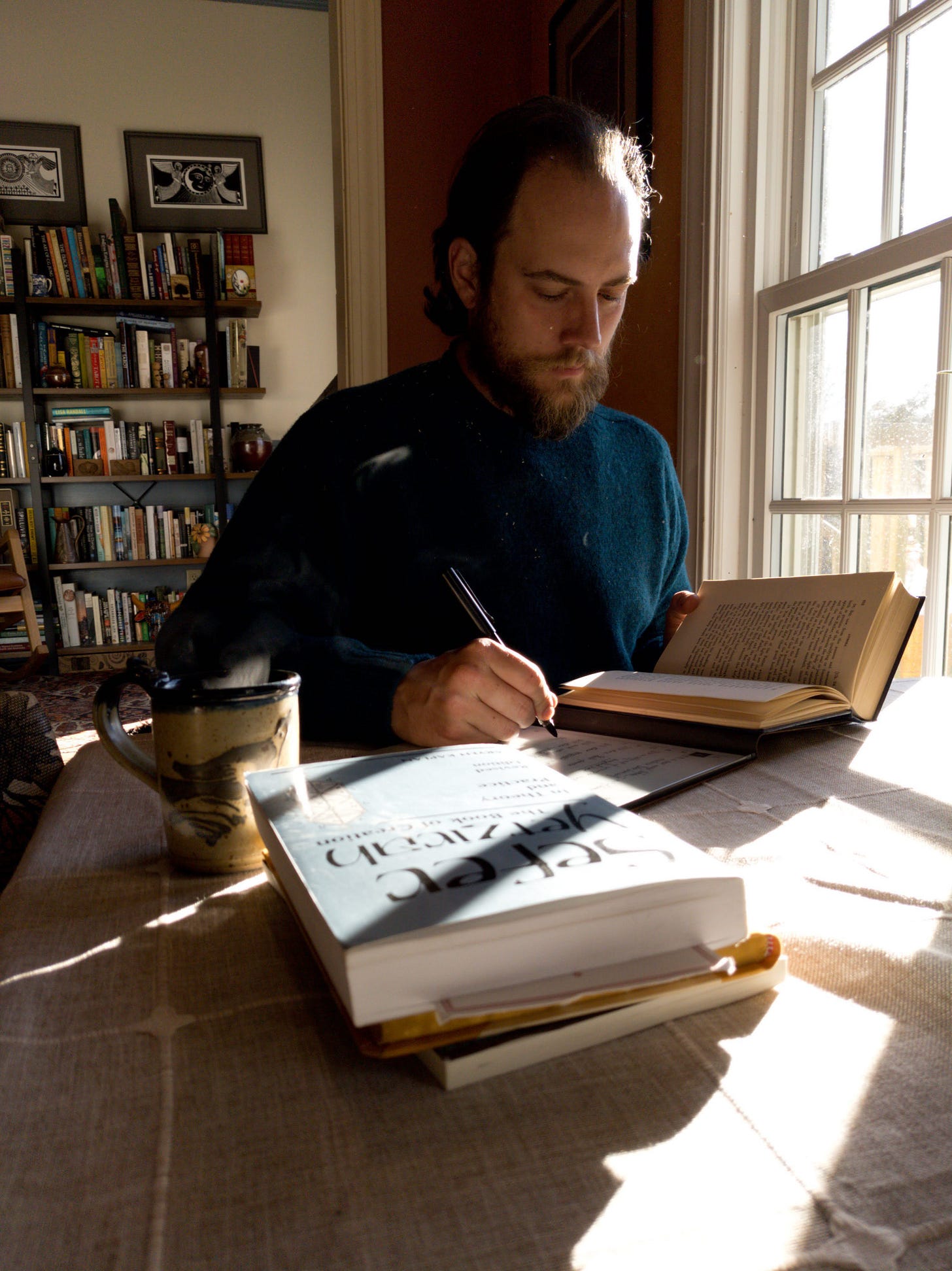

JPI: You're a farmer, an author, an artist and the creative director at JPI. Indeed, you’ve been managing JPI’s presence on Substack since May 2023, plus publishing your own writing elsewhere. Tell us what inspired you to start writing?

Stewart Lundy: I started JPI’s Substack account on a lark. I had no experience with this platform (or anything of its kind) but I had a lot I had learned. When I have free time, I’m studying old texts, or a new language.. or starting a new Substack account! While it may seem like I live three lives simultaneously, I have cultivated a “resting state” of activity. I am a candle burning at both ends.

Rudolf Steiner said something somewhere about how you shouldn’t write about esoteric themes until after the age of thirty-five. I sensed keenly that my “assimilation” stage of life was drawing to a close, so up to that tipping point, I binged on everything I could find – as if I would only be able to return to the byways I had already explored in the second half of life. While I presented on herbalism and biodynamics, I restrained myself from speaking on most deeper themes except in one-on-one settings. So, instead of talking openly about what I was learning and experiencing, I suppressed most of it. Steiner was right about that, but you don’t know until you know.

After a certain point everything began to flow, making connections between all sorts of disparate fragments I’d accumulated over the years. It feels like having collected hundreds of puzzle pieces and now having the front of the puzzle box. I don’t have all the pieces, but I can see more or less where the few pieces I’ve found do fit.

But that’s the long and short of it: I wanted to write, but I didn’t have enough experience to say anything fruitful. Having lived a little more, hopefully what I share now is of a bit more use.

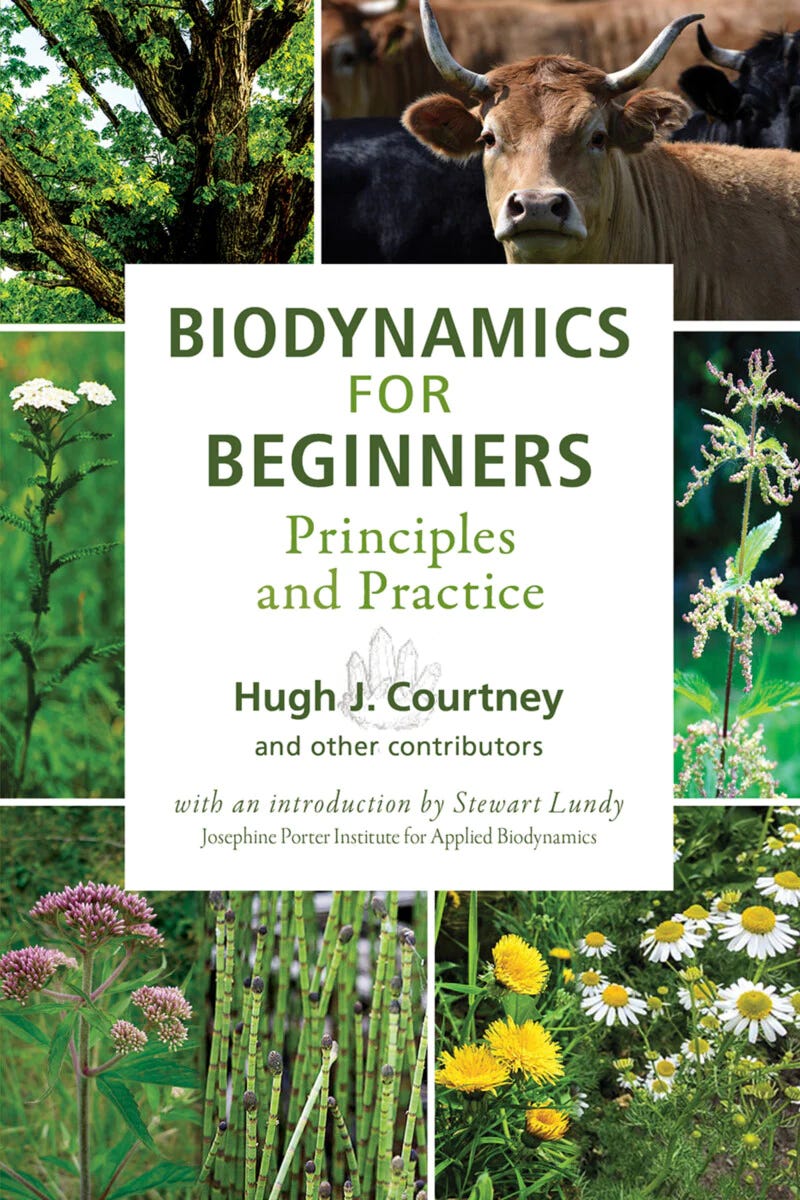

Q: This book is a collection of previous articles from JPI’s flagship publication, Applied Biodynamics. Why did you choose the articles you selected for publication? What were the parameters that guided those choices? What did you hope to achieve with this collection?

A: During Hugh Courtney’s practicums, he would give a handout to attendees of his favorite articles from Applied Biodynamics. These pieces needed revision and editing, and were notably missing certain elements, but the idea was there as a coherent whole. As he would say every year he handed them out, the articles were the property of JPI, but he hoped to transcribe them and publish them as a book. This never happened, so I have attempted to do them justice here.

Hugh had hand-selected articles for almost every single biodynamic preparation, but a few were missing. I chose what seemed like the best representation to fill the gaps. I wanted to offer a coherent picture of what Applied Biodynamics has been and where it came from to be able to deliver a book worth reading for years to come.

Most of the work I did on this book occurred in 2022 – before our Substack presence was even an idea in my mind. I had decided that there needed to be a new book for the centennial of biodynamics. This is one attempt at that.

Q: Is there a particular quote, point, or lesson from among the collection of articles that stands out to you that might guide and inspire us?

A: A line from Hugh Courtney stands out: “If one tries to separate the animal influence from the growing of our food, then the consequences may well be that in a short time we will not be able to grow food.” This idea goes exactly against the general impulse which insults the cow by blaming her for emissions when it is exclusively the avarice of humans that leads to imbalances. The cow, left to herself, only eats what is first sequestered by plants as energy. The cow’s “farts” are always less than the plant accumulated, provided the plant is receptive to the influx of cosmic energy – sunlight, first and foremost. The rich soils of the midwest were not created by a “vegetarian” ecosystem, but was an intimate relationship between bison and human beings. We cannot exclude animals from ecosystems anymore than we can exclude human beings from ecology. We human beings are both a product of our ecosystems and the culmination of a spiritual process. You might say that it is our task – or even our cross – to bear the self-awareness of the Earth within ourselves. This is not about dissociation, but about reintegration. It is also not washing our hands like Pontius Pilate. No, we must own our responsibility both for the damages we have wrought on Mother Earth and take the necessary steps to restore her to life by demanding less of her and giving more back to her. Speaking from the heart, I hope she can forgive us.

Q: Not only are you an author, but also an artist? Share a bit about your work as an artist, as well as the inspiration behind the art you selected for this book?

A: I’ve always drawn, using various mediums. When I was a child, the neighbor boy wanted to play with my cap guns. I didn’t care because these bored me. Instead, I would paint flowers. I have a tendency to “overwork” art by spending too much time on it. I find writing more forgiving when it comes to revisions. It’s hard to undo a brushstroke or a piece of wood removed from a carving.

The artwork for the book comes through a nature artist, Jenna Collins, whom I personally commissioned to make these pieces. The black and white versions are for this book, though I have full color versions perhaps for some other book someday. Many other artists could have done this work, but this is part of a gift I can offer to the biodynamic community at large.

Q: A Dose of Clay was the original working title for the book. What inspired that title? What did it mean to you?

A: Rudolf Steiner mentions a “dose of clay” in the Agriculture Course and promises to give indications about how to treat soil with clay. At least within the body of the Agriculture Course, this did not happen explicitly. Some reports seem to indicate that Ehrenfried Pfeiffer was given a recipe using clay in horns. This is something Hugh Courtney championed for a while, but later decided had been an error. He was no longer an advocate of “horn clay” by the end of his life, but rather saw that as another form of 501, which Steiner says can be made from virtually any silicate. By the end of his life, Hugh considered the colloidal claylike quality of the preparations themselves to be the “dose of clay” that Steiner had indicated. Clay aids what Steiner calls the “cosmic upward stream” which is the upward movement of potential energy discharged as kinetic energy in the growth of plants.

Q: You have been a biodynamic farmer for at least 10 years. I understand that Hugh Courtney, the primary author featured in the book, was an early biodynamic teacher of yours, as well as many others. Could you tell us a little about him? Why did you study with him? Would you consider him a mentor? Why?

A: Even though his farm was a seven hour drive away from me, he was the only person anywhere near me offering anything like this. I’d go to his farm for a week to ten days every year to learn. By the end, I was even asked if it was still worth it for me — and whether I had anything to learn there anymore. I replied that I wouldn’t still be there if I weren’t still learning.

Hugh Courtney had strong opinions, but if you asked him a question – and I bombarded him with questions – he was likely to default to saying, “Let me know what you find out!” While this isn’t a particularly satisfying answer, it deflected me back to my own research and my own experience. I certainly learned much of the practical side of making preparations from Hugh Courtney. Much of what he taught me persists here at JPI today.

Q: What initially drew you to biodynamics?

A: I had subscribed to Acres, USA, which remains a beacon of light for eco-agriculture. I was deeply skeptical about biodynamics, but my wife showed me an article by Hugh Lovel concerning the moon governing tides and therefore also governing the rise and fall of sap in plants. In that moment, it “clicked,” and I had to learn more. I read half a dozen books, and almost gave up but then I discovered the work of Maria Thun and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. A whole new world opened up! Since then, I have made it my business to read virtually every single biodynamic book in English, as well as a few in German. This was an enormous task, though it’s now no longer something I try to keep up with anymore. My initial curiosity has been sated, and I am now far more concerned with promulgating biodynamic concepts and putting them into practice.

Q: Did you farm in other ways before you began to practice biodynamics?

A: We began farming with more of a homestead aspiration. There’s a germ of selfishness in the goal of self-sufficiency – a kind of hubris of not needing anyone else. Of course, that’s ridiculous. Even if I were to attain total (apparent) self-sufficiency, the tools I brought with me, the skills, and even the language in which I think are all social debts. There is no such thing as a totally self-sufficient individual, nor should that even be a goal. Better than that, we learn to work together with people without having to quibble disagreeably about subjective opinions. If we share common ideals – such as beauty, goodness, truth, and freedom – we should work towards those.

When we started our farm, we began with a no-chemical mindset and certain permaculture influences. But even those fell short of what’s necessary. No-till has its limitations, as does anything we might try to do. So I shifted to minimal disturbance and to leaving the “middle zone” alone. Deep ripping and shallow cultivation while keeping the middle root zone of the soil intact has led to much better results.

As the farmer moves through the garden, the plants experience us like a moonglow. If our mood is dark and stormy, we bring a shadow to the garden. If we are grateful when we are tending the plants, we bring spiritual sunlight into everything we tend.

Q: What does the practice of biodynamics mean to you energetically? You’ve written about the farm organism–how the land and the farmer change with the practice of biodynamics. How has that practice changed you?

A: For me, the farmer is the directing “I” of the farm organism. Without the farmer tending the farm, there is no farm at all! It quickly returns to a wild space, whether a forest or a desert. If you imagine watching the farmer moving overhead and fast-forward the footage, you watch an expansive rhythm every day during summer, and then the rhythm contracts during winter. The movements of the farmer are like the circulation of the blood on the farm. Yes, the animals have their place and their special work but, without the farmer, it all would go belly-up. Now, this doesn’t mean that the farmer should be the ego of the farm. An egotistical farmer will have an overbearing influence on the farm, preventing any wild spaces. Ultimately this only harms the farm. A farmer without enough directional influence, however, creates a space that is a kind of wild beauty but is primarily food for the birds. The successful farmer is a nexus between two worlds. We need the wild world, yet we can’t allow the wild to take over the garden or there would be all kinds of plants we couldn’t eat choking out our food.

Everything the farmer touches is imbued with the quality of the individual’s mood, imagination, and thoughts. If you are tending plants in a bad mood, it’s not good for you and it’s not good for the plants. If you were to imagine “seeing” like a plant, they are blind, but they experience our warmth. Since plants are “blind” in a sense, imagine closing your eyes and everything being dark. As the farmer moves through the garden, the plants experience us like a moonglow. If our mood is dark and stormy, we bring a shadow to the garden. If we are grateful when we are tending the plants, we bring spiritual sunlight into everything we tend.

Q: We’re approaching the 100-year anniversary of Steiner’s gift of the Agriculture Course. What do you hope to see happen in the next 10, 50, 100 years for farming in the United States and around the world?

A: Ehrenfried Pfeiffer wrote somewhere that any soil below 2% tends quickly towards desertification. As this is the condition of most of our soils worldwide, we can't afford to abandon land to nature now. The Earth requires our participation to create oases of biodiversity, a new kind of ecological “monasticism” in the face of an impending dark age. Farm organisms here are spaces from which biodiversity can reemerge when the time is right – when humanity is ready. From these isolated bastions of culture, humanity may return again to prosper under new conditions, but after enormous suffering.

The wisdom of the desert will be what preserves humanity.

The key people and places to learn from are pioneers like Jose Aviña in Mexico, Liron Israely in Israel, Joseluis Ortiz in New Mexico, SEKEM in Egypt, and the late Alex Podolinsky in Australia. There are many others I cannot begin to name now. The wisdom of the desert will be what preserves humanity.

As climate chaos continues to wreak havoc, we will need to learn from the wellsprings of experiential knowledge of those who turn deserts green. Conservation tillage only became a significant governmental policy after the Dust Bowl. We are likely to see true widespread regenerative practices after we've nearly ruined the environment.

Human beings only learn after making mistakes, and collective humanity all the more so. After a near collapse, we may learn how to turn our extractive technology into terraforming, transforming desecrated landscapes into sources of new life. After striving to extract everything we can from the earth – and having succeeded in doing so! – I see our center of gravity shifting and we will be striving to bring spiritual life back into the earth instead of merely floating away into the ethers. My greatest hope is that by desecrating our planet, we collectively learn how to regenerate dead planets by starting with this one and using that technology to turn new planets green. Instead of the imperialistic aims of technocrats, a galactic call to turn other planets and their moons into gardens. Imagine the moon above us one day full of blue lakes and rivers and lush with greenery.

In ten years it will be hard to farm, especially if we haven't planted perennial crops that can survive extremes in winter and summer. The USA now replants forests with trees several zones warmer, in preparation for unavoidable changes. Even with climate change, the principles of biodynamics will remain the same.

One promising element is that the evils of industrial society require perpetual maintenance. Asphalt only seems permanent because of continuous repairs. Given only a few years, dandelions, grasses, and trees dominate again. Anything living not only grows, it proliferates ever more life. Our contrived attempts at artificial permanence are little more than a Tower of Babel. Perhaps one of the best things that could happen ecologically would be all of us unable to prevent lawns from becoming forests again. Were this to happen, almost no one would welcome it, but the world's ecosystems would rejoice.

Rudolf Steiner said somewhere that without human beings the Earth would have died much earlier. Given our modern abuses of the Earth, this seems absurd. However, indigenous relationships with the land not only lived sustainably but were regularly regenerative, fostering more life for the future.

I met a man at the 2023 BDA conference who urged me to plant hybrid willows. Against the idea that they “use up” water, he said quite the opposite: willows draw water up from the depths, providing water to the topsoil even in very dry areas, maintaining capillary action where the prevailing climate might have other ideas. Extrapolating from this, one might almost suggest that where willows grow, no desert will easily form. These trees also protect in cases of flooding. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer noted that Salix spp. willows can evaporate 5000 gallons of water per day each in a flood. It is neglected species like this and their ancient relationship with human beings that will sustain us into a certainly uncertain future.

In fifty years, many of the forests we knew as children may well be declining or gone. The most fruitful actions we can take now is by assuming that we can't avert climate catastrophe and start planting today for a climate insecure future. The ideas of biodynamics that will survive are its principles and practices, adapted to new climatic conditions.This is part of why I think it's so important to get the ideas out there — and in print form.

In a hundred years we will need to remember what it was like to live in Eden. We can approach the garden by practicing being there now.

Q: Do you see Steiner’s vision as presented in the Agriculture Course being achieved?

A: Biodynamics isn’t likely to go away as a spiritual influence. Its effects may never dominate industrial agriculture, but our insistence not just on the physical, chemical, and biological but also the spiritual remains an important theme to champion. As the farm is not a farm without the human-I, what is the soil without the soul?

People are hungry for something that reminds us of our significance – that everything in this human experience of value is not only preserved but grows over our lives. Rocks love to be and know how to exist. But plants love to grow and proliferate and know that experience. Animals feel and move and engage in an even more dazzling display of inner experiences. But it is only the human being – in you – that can recognize the world as a world. Only you can recognize a rock, plant, and animal as having these distinct experiences of our shared world. This capacity to think about the world is the basis of human freedom: the fact that we can pause between stimuli and reaction and reconsider our course of action. We don’t merely have to act based on instinct, but can choose based on principles like the Golden Rule.

Biodynamics doesn’t tell you what to do with your hard-earned freedom, because biodynamics is founded on a fundamental trust in the human being.

The future of Biodynamics is to champion the soul of agriculture. If it is successful, it will put itself out of business because enough regenerative practices will incorporate the meaningful elements of Biodynamics. This is not a pyramid scheme or model that demands anything of participants. On the contrary, biodynamics offers a way for you to have a platform from which to be free of coercive influences by helping the farm become more of a self-contained individuality able to source its own fertility needs from within its own borders. Someone manipulated and coerced cannot be trusted to act freely, because they are not being given human dignity. But someone who is truly free in a spiritual way can be trusted absolutely to remain loyal to their principles. Biodynamics doesn’t tell you what to do with your hard-earned freedom, because biodynamics is founded on a fundamental trust in the human being.

For me, I’d love to see a time when the influence of biodynamics had become so subtle – so etheric – that it was both nurtured everywhere and yet discussed nowhere. I look forward to biodynamics transforming into an etheric star.

Q: You are JPI’s creative director but it sounds like you doing that and more for the institute. What variety of activities are you involved in? Where do you hope JPI will be in five years?

A: I’m involved at almost every level, as much as I’m able to be. I decided to give myself to this work without reservation, and that is what I am now doing. There’s so much more to know, and I only have a small drop in the vast ocean of human experience. I appreciate the support of the biodynamic community at large, as well as the JPI staff and board. None of this would be possible without all of you.

We will become an “incubator farm” demonstrating biodynamic practices, donating produce to the local community, and showing ourselves to be a real living farm organism able to reproduce by gestating and giving birth to new farmers.

JPI will be performing plant trials every season, demonstrating the effectiveness of different biodynamic preparations on plant growth. In addition to this we will be performing more picture-forming methods including chromatography along the lines of Ehrenfried Pfeiffer as well as some surprises born out of the anthroposophical impulse in Europe. In five years, I see JPI with a sensitive crystallization laboratory and offering assessment to wineries and anyone serious about quality. We will become an “incubator farm” demonstrating biodynamic practices, donating produce to the local community, and showing ourselves to be a real living farm organism able to reproduce by gestating and giving birth to new farmers.

Q: What's in the works for you creatively - can we look forward to another book soon?

A: While I have a translation of the Agriculture Course in the works, that has been put on the back burner because of the amount of time I have to dedicate to JPI now. My translation focuses on clear language and practical agricultural applications. Many people pick up the Agriculture Course and have a hard time seeing how it’s about farming! That’s a problem for me. While I have no interest in “demythologizing” Steiner, a farmer should be able to pick up the Agriculture Course and, even if not immediately able to grasp all the undergirding ideas, understand how and why to use it.

I’m to a point where fourteen years of intensive farming and unrelenting study have given me the fruits of many other people’s wisdom. It is time for me to write my own biodynamic book. Not a revision of Steiner, but agriculture as I see it. I haven’t written a word of it yet – or maybe that’s what these Substack articles are going to become? Who knows! Maybe if I take a sabbatical from farming for one year I can get a book written.

Hugh Courtney liked to say that he was in the business of putting himself out of business. That’s an idea that remains a guiding light for me: I want so many people to be making preparations that JPI is obsolete and can metamorphosize into something else. I even think the same thing about my own farm and educational work: it would be wonderful if so many farmers were growing vegetables and livestock with the tools that I’m sharing that I myself become irrelevant and have to focus on something new to offer the world.

Karina, thank you so much for organizing this interview! I am moved.

Stewart - o my goodness. How amazing. Thank you for the book. A line from above, the Hugh Courtney quote, stands out: “If one tries to separate the animal influence from the growing of our food, then the consequences may well be that in a short time we will not be able to grow food.” I have been saying the same thing a lot lately. I have compiled a set of peer reviewed articles about the problems with food grown in the absence of insects. The nutritional levels of organic food grown in clean lab type settings, like hydroponics, etc. without the influence of insects (earthworms, little bugs biting the leaves) is similar to the nutritional levels of conventional food. The animals biting and interacting and pollinating the plants make them more themselves. Harold McGee the food scientist talks about how bruising a leaf or pinching back herbs causes the plant to produce more of the volatile oils that both fortify the plant immune system and make it more smelly and tasty and yummy to us. The animal world makes plants more themselves.

M said yesterday that you can judge the health of your soil by the insect life.

Pfeiffer is my jam. That compost starter he has with all the preps & lactobacteria whatever is the bomb and I can't believe it's not out there in every waste management facility in the world.

Yes to writing your own book next. I feel ready to do the same. My accomplishment so far has been to open a document and name it Gardening Book and save it in a file called Gardening Book in my writing folder. Good luck achieving this milestone yourself some day.

I would like you to teach more about history and the intersection b/t religions and practices all over the world and time. I like recipes that work in the spiritual and material world (so I guess that's under the category of Spiritual Practice), and Applied Biodynamics has always been good for recipes. I like storytelling and your synthesis to ideas, people, and projects far and wide. It's always good to hear your recommendations for projects, like citing Joseluis and SEKEM and so I always appreciate a good book or website to check out. Thank you for asking.

OK now I'm really going to be late to my next thing. This article was worth it though.

hi Stewart and all the team at JPI

I read the first section of what you sent this morning and with a full springtime influx of activities, including garnering the commission of my career at a wonderful historic property, Plaza Chamisal off the Acequia Madre here in Santa Fe, to renew and design for a mature garden and a new garden/patio area - plus having to move on the 15th of April - after a charming place down the street from where I live in South Capitol - that I had been coveting for months - taking gifts to the owners - who live near Mesa Verde - re. leasing a house with a mature garden - it just fizzled away as they uncharteristically - didn't not respond to my outreaches. I love what Hugh related in his common sense manner with poignancy regarding our beloved gift from cows. We have made BD compost for over 25 years here in Santa Fe and I have come to love the fragrance of cow manure used in our mix. However, when our hero Dustin Maloney - who had supplied our manure from his father-in-laws dairy in Albuq. NM - transitioned from suicide - leaving a wife and child - as he got over extended with all the government pressures and little support from our governor - we lost a great deal. It took me over one and half years to locate another location for a semi truck of good quality cow manure. Although in the planning since January - we still haven't received the goods - freight prices keep rising! Soon I imagine. In our area the best time to make compost is in the autumn when the manure is fresh but more dry and not so heavy -Dustin would use his backhoe and put the piles in the sun ! Well on to other tasks here at pre dawn. Hope I have some time to return to the beginnings of a informative and well presented interview. quanto e bella la prossima primavera Maggie Lee gardengaia.com