By our house is a tall loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) that my wife and her father planted many years ago. It stands tall, shedding pine needles (and ubiquitous pollen) during varying seasons. There is such a stark difference in the growth of a pine tree versus, say, an oak. Not only are the leaves so incredibly different, but the trees behave in such radically distinct ways. An oak tree, in Ehrenfried Pfeiffer’s words, is one of the only trees that thrives in monoculture because oaks produce such beautifully balanced soil. Oaks thrive in artificial monoculture, yes, but they do not naturally occur that way: the soil around oaks is so hospitable you see dozens of species germinating under its magnanimous shade.

Oaks can thrive healthily in a vast stand, but they naturally tend to generate diverse polyculture. Oak trees are not the best at any one thing: they aren’t the best firewood, they aren’t the best building material, they aren’t even necessarily the best tanning material, nor are they the best food source — and yet, precisely because oaks have remained “generalists” they are the most like human beings in the plant world. By not specializing, they are not the best in any one given category, but they are one of the very best trees overall.1

Imagine planetary associations as an older mode of taxonomy.

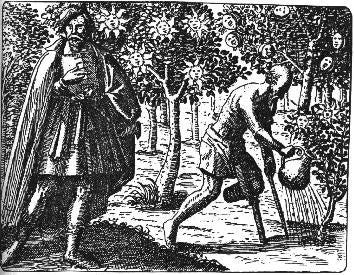

By contrast to the welcoming presence of oaks, pines tend to be quite the opposite. Instead of many species germinating under their boughs, we mostly find more pines growing around pines. They make conditions more suitable for their own kind, so there is a kind of severity to these trees, if not quite outright inhospitality. Severity is a trait of Saturn, who is said to “govern” such trees. For anyone who struggles with the idea of planetary “governances” of this or that plant or organ, one can easily set the term aside altogether. Imagine planetary associations as an older mode of taxonomy. We classify in our own way these days, but there was another time when we classified species according to their characteristics. We might say that a Saturn “governed” plant is a species that shares many traits with what is conventionally associated with Saturn. Notably, the unwelcoming quality of pine needles does not last if they are composted. The antipathy of pine needles once composted enough, becomes their opposite. Maria Thun remarks in her research that pine needles if composted long enough, make one of the very best composts. Alan Chadwick, by contrast, says that one of the best places to build a compost pile is in the vicinity of oak trees — the mere presence of their atmospheric influence is enough to help make balanced compost piles.

In my experience, oak leaves make beautifully balanced compost. It is not overly sympathetic or antipathetic — but something equanimous. The opposite of balance is balance, so when oak leaves are composted, they remain a balanced compost. The one-sidedness of pine needles lends to their more immediate medicinal properties and also their remarkable use as compost later.

Upside Down Biodynamics

“[T]he fragrant flowers of a large number of plants are really organs of smell; they’re vegetable organs of smell which are extraordinarily sensitive. And what do they smell? They smell the omnipresent world’s aroma.” - R. Steiner

Evergreen trees are traditionally “governed” by Saturn. They often shed branches (like the crippled god Saturn), and they remain warm during the winter. The reflective warmth from pine needles maintains a microclimate of warmth below the tree. Compare this to the unprotected soil under a deciduous tree like an oak during winter, and there is a marked difference.

One of the best little booklets for anyone looking to manage trees and avoid serious mistakes is Shigo’s 100 Tree Myths. I depart a bit from his recommendations, but only mildly, I hope. Whenever a wound is made on a tree, it never “heals” the way you or I might heal. Instead, the exposed wood dies, experiences weathering conditions, and then, if all goes well, the outer bark entombs the deadened wood. But that deadened wood remains dead within the tree, leaving inner “scars” to varying degrees. If a branch is not properly cut, this can leave a spear of deadwood that pierces right into the heart of a tree, which is not just a structural problem long-term but an opportunity for disease.

In biodynamics, many people use tree paste. The original recipe by Pfeiffer for this was equal parts cow manure, sand, and clay. The recipe has evolved, especially for those who wish the paste to remain on the tree longer and do not wish to use uncomposted manure.

Biodynamic Tree Paste Recipe

Tree paste is a way to revitalize trees and orchards. It contains clay, the Pfeiffer field spray, the influence of all the biodynamic compost preparations, and fermented Equisetum arvense which helps combat fungus in orchards and vineyards.

But while this is an excellent remedy, it has never adequately addressed the issue of a large area of exposed wood on a wounded tree, for example, when a goat gets out and strips half the bark off the trunk of your chestnut trees. Do we just wait for it to heal? Or do we intervene to minimize the damage?

You will often find bees collecting sap from trees, which they take back to their hives as propolis — a kind of resin that not only preserves their home but has a vital function in their collective immune system. Hollow trees that boast resident bees inside them live decades longer, largely thanks to this imported and maintained layer of resinous propolis.

From this image, I was inspired to take the hard resin from various trees around the property: pine, cherry, and plum, and melt them into a paste, which I might use to cover the wounds from pruning trees. This doesn’t contradict anything that the conventional biodynamic “tree paste” does, but it acts as a sealant on new wounds. While we may not have time to cover all the wounds we make when pruning and while this may not be news to all our readers, it is new to me. There are many uses for resin.

As resinous sap is often produced by the pruning intervention of “Saturn”, there is a remedy being offered for other trees that do not produce enough of their own resin to function as a sealant for their wounds. We can transpose the qualities of one tree to another.

We tried to dissolve the resin we collected with cold vinegar, which did not work the way I wanted it to. I started over and used high-proof alcohol and put it in a small saucepan over heat. With patient stirring (and with the help of an immersion blender), the resin melted enough that it became a thick gooey paste.

I mixed the resin with alcohol to make it easier to store and spread later. You could heat the resin and rush about your orchard trying to use it before it cooled and hardened again, but I wanted something I’d be able to use whenever I wanted and to use in cold weather. A small brush, and each exposed wound can be sealed with resin almost as quickly as it is made.

I’ll be monitoring these and sharing updates this coming season to see how this turns out and what kind of lasting benefits it provides.

Collecting pine “sap” (resin):

Tapping a pine tree for sap:

For those interested in learning more about this wonderful tree, I recommend Oak: The Frame of Civilization by William Bryant Logan