Cosmic Forces & Earthly Substance

revisiting the plant, further meditations on the Agriculture Course

“The flower exists for its own sake,—not for the fruit’s sake. The production of the fruit is an added honour to it—is a granted consolation to us for its death. But the flower is the end of the seed,—not the seed of the flower.”1 - John Ruskin, Proserpina

Matter as we know it is always a precipitate out of what was formerly dynamic energy. As dew condenses from the atmosphere and wood grows up out of the earth, there are two streams of materialization, whether this becomes a substance formed from the cosmos (e.g., oils or sugars), or heavier coalescences (e.g., coral or bones). In each case, what appears as substance is, relatively speaking, dead compared to the unimaginably long journey it took before becoming materialized. It is rather easy to see how wood was once a softer, flowing process in a living tree that has “died” and solidified. It is somewhat harder to perceive how this is true of the entire sense-perceptible material world, but it is nonetheless true. In sugar, light has been arrested — it has “died” into a solidified form that contains the same energy locked up and waiting to be released again.

In the Agriculture Course, Steiner offers a difficult picture of forces versus substances. He describes the root as predominantly earthly substance whereas the delicate petals of the flower are cosmic substance. And yet the opposite forces work in each pole. What does this mean? It means that lime and associated carbonates help form the densely mineralized solidity of the root, but the lime-like grasping activity of the reproductive center of the flower is the dynamics of calcium not as a crystallized deposit of coarse substance but rather as something that operates in fine diluted doses in an almost homeopathic (or in an enzymatic / stimulant) way. Conversely, the flower is formed out of the air, light, and warmth that the plant has condensed from the cosmos this year, while the sugars radiated out of the root are a direct expression of cosmic energy at work as an activity within the soil.

Around the seed often arises a sweet fruit which is full of the cosmic forces of air, light, and warmth that the plant has accumulated — and yet they have been accumulated as an “external” growth on the plant. In spite of how much energy the plant puts into the sweet fruits, it cannot later go and make a “withdrawal” from what it deposited. In this sense, it has only just brushed up against the possibility of internalizing these outer planetary forces — but it can’t make use of them having collected them. As Gerbert Grohman says, “Nature has destined the fruits for the stomachs of hungry animals. The plant could do without the fruit. They are given as an almost useless (to the plant) excretory product to the hungry environment. However, plant and animal kingdoms form a living whole in which one cannot be thought of without the other.”2 By contrast, an animal can accumulate cosmic substance and make use of it again. “Oh, the pigs, the fat pigs and sows—what heavenly creatures they are! In their fat body—insofar as it is not nerves-and-senses system—they have nothing but cosmic substance.”3 A pig accumulates enormous warmth, but cannot direct it upwards to the head for spiritual thought. Pigs are extremely clever, but in a “kidney-thinking” way.4 They are good at solving problems that make them feel good at the end, but with no capacity for higher spiritual contemplation. As modern consciousness tends to be rooted in the kidneys — exoterically in the fight-or-flight response, esoterically in the solar plexus chakra, which is about how the external sense-perceptible world makes us feel. The pig appears to us as the most intelligent because it appears most like us in our current prejudices, though in medieval times the pig was used as a moral lesson against gluttony. Unable to direct warmth to the brain for spiritual thought, the pig instead accumulates an enormous deposit of backfat. Thinking is hard work. If it weren’t hard work, everyone would do it. A pig cannot sweat and thus requires a wallow, not because it loves filth but because it wishes to cool itself. Because a pig cannot direct this enormous amount of warmth within itself, it cannot attain to pure thinking. Nonetheless, an animal fully encapsulates the process that a plant only brushes up against. A plant can accumulate cosmic substance, but it cannot make use of it. An animal is like a plant that can amass plump fruits and then eat them when it gets hungry. In this sense, animals have “internalized” more of the cosmos. To the degree that any organism has done this, it is more or less “emancipated” as a fully formed microcosmic image of the cosmos. When an organism contains a mirror image of the All, it, too, becomes free.

“The peach is in this respect the best general type,—the woolly skin being the outer one of the husk; the part we eat, the central substance of the husk; and the hard shell of the stone, the inner skin of the husk. The bitter kernel within is the seed.”5

Such polarities are all relational — they are true on a particular level and always relative to something else on its own level. It is not enough to sketch these out as abstract systems through which everything can automatically be filtered. To do so places the dead system between us and the living phenomenon itself. We can lose sight of the forest because of the trees, but we can also lose sight of the trees because of the forest: we can get lost in the particulars or lost in generalizations. But the living phenomenon is a marriage of the two and forbids one-sidedness if you give it your full attention. Relative to the sweet fruit of a peach, the bitter kernel expresses the “inner planets” while the edible flesh expresses the “outer planets” — but if you shift your gaze to the seed itself as a whole, there exists within it a reserve of cosmic energy and an embryo.

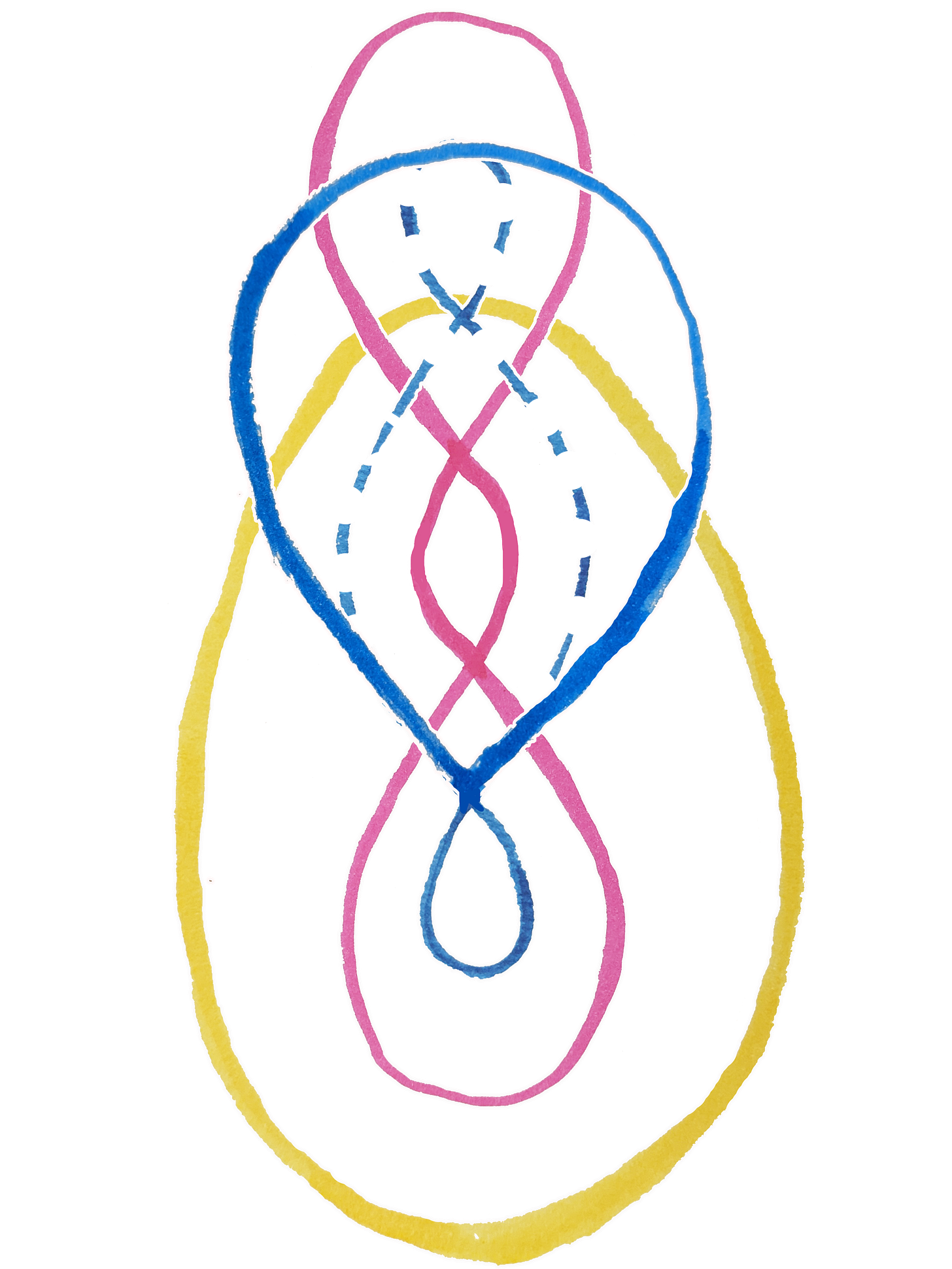

This is why the seed itself can be represented by the hieroglyphic monad: all planets are at work within each living whole precisely because it is a whole. Expanded outwards, the “All in All” is the wholeness of all wholes — which is what religions call “God.” Like nested Russian dolls, the whole is made up not of various fragments but of smaller wholes. This is why understanding even a single plant in a truly spiritual way becomes a “key” to the entire cosmos if applied correctly.

When a plant produces a flower, it is a kind of “rupture,” which is why trees like American Chestnut can grow up until the point of bud break or an actual wound, at which point they invariably become infected with chestnut blight. Once the interior of the plant is exposed to the environment in either of these ways, the plant becomes easily becomes infected. We cannot consider the flower merely a “part” of the plant. “A flower is to the vegetable substance what a crystal is to the mineral.”6 Or, as Goethe says, “The butterfly is a flying flower, The flower a tethered butterfly.” The flower is born out of the plant the way the butterfly is born out of the caterpillar. Where is the green form once the flower bursts open? This is especially clear for the papillonicae family (legumes).

As the flower opens, nectar is finally offered up to the atmosphere in a way that it has been offered all along to the rhizosphere. Nectar infused with cosmic power has been permeating the entire plant, carrying the power of the sun down into the soil where the complexity of life exceeds the powers of human imagination. In the root and the flower, we have a mirror image. Relative to the woody root, the flower is a delicate, ephemeral thing. And yet, the root and the flower share an inner kinship. The substantiality of the root is primarily composed of mineral salts (carbonates) and humus (the sunlight of yesteryear). And yet out of the flower is a small radiant center releasing cosmic forces not unlike how the root does in a more dominant way. However, the chthonic grasping of the root is almost invisible in the flower because it is hidden within the grasping reproductive power.

Roots clearly have the most “grasping” form, but, in general, that is the end of it. The roots grasp tenaciously to the earth, but then they become oddly generous. Yes, the root takes to a degree for its substantiality, but at the same time it gives away an enormous amount of cosmic forces to the earth. This is why Alan Chadwick can say, “soil in that bed is better now since the plants dealt with it, than when you prepared it and put the plants in and left them to it. It is superior. It is more fertile.”7 Through consistent and rapid succession crop rotation, a garden bed is made more fertile, particularly by crops that do not reach flowering. Why? Once a blossom has opened, there is a rupture in the plant and nectar is radiating up and away. If you are transplanting anything from flats, you must pinch off all the early blossoms so that the nectar remains contained and instead feeds the roots. This is much the same principle as pinching off garlic scapes so you get bigger garlic bulbs. While plants are in their establishment phase, you must be vigilant to remove their blossoms. When plants bear premature offspring, their total limit of possibility is restricted. Yes, you get early fruit, but that’s usually all you get from such a plant. Pinching off premature blossoms is delayed gratification in the garden — it stores up treasures in the future. A plant that isn’t well-rooted has no business producing offspring. In the fruit we have the capacity to hold and retain the mood of the cosmos. “Instead of ‘mood,’ we might say ‘atmosphere.’ A musical work can draw us into an imagined space with a certain atmosphere.’8 Specifically with the outer planets, we have the capacity to accumulate and maintain an inner atmosphere, which we experience as sweet fruit.

Moreover, if you are tending tomatoes and you notice any blossom end rot, this is like a permanently open wound. Since the fruit with blossom end rot is unable to contain the acids that are ripening into fruit, they immediately start rotting. The fruit turns a premature color, but the plant continues to pour nectar into it — and for nought. Because the fruit is unable to contain that upward nectarine stream, such fruits are like large parasites on the entire organism of the plant. If you see any tomatoes with blossom end rot, they should be removed immediately. This does not address why such a thing occurs nor does it answer how to prevent it, but if it shows up, those rotting fruits consume an inordinate amount of energy from the plant. The plant really does try its best to fill it up the ruptured fruit with nutrition, but it’s like trying to fill a bottomless pit — or a balloon with a hole in it. The plant will continue to sacrifice energy to a useless fruit — it must be plucked off if you do not want to exhaust your plants.

Your Darkness Shall be Turned into Light

In biodynamics, we must begin where the plant begins: with the root. In the development of a plant, the first thing to emerge is its root, followed by its green cotyledons, and finally by its flower with its fruit. In this trichotomy, we see one aspect growing downward and two others growing upward.

By the same token, Chadwick warns us that when using cover crops that we must mow them down when they reach 20% blossom. Once more, when plants have open flowers they begin to send nectar up and away from the earth. Since the purpose of a cover crop is bringing into the earth cosmic light, we cannot allow them to go to flower but must nip that in the bud. Steve Solomon even warns that legumes, if allowed to go to seed, often leave a net loss of nitrogen in the soil. And why wouldn’t that be the case? Those nitrogen-fixing nodules aren’t there for you! The plant has quite other designs in mind. So, if you want to keep those nitrogenous nodules, you must abort the plant’s normal life cycle and cut it short.

The “saltiest” part of the plant is the roots, as the earth element tends downwards. The most aromatic aspect of the plant tends to be the leaves and flowers, as oils tend to rise:

“The plant in growing from the soil in its year is at first really growing with the powers which the sun has given to the earth the year before if not earlier, for the plant takes its dynamics from the soil. These dynamics taken from the soil can be traced as far as the ovary, as far as seed development. We therefore only have a genuine botany that is in accord with the whole physiology if we take account not only the dynamics of warmth and light and of light conditions in the year when the plant is growing, but starting from the root base ourselves on the dynamics of light and warmth at least in the year before. We can trace this as far as the ovary, so that we have something in the ovary which happened the year before still active from the year before. If on the other hand you study the foliage, and even more the sepals and petals, you will in the leaves find a compromise, I'd say, between the dynamics of the year before and the dynamics of the current year. The leaves have in them the element pushing up from the soil and the influences of the environment. In petals the current year finally shows itself in its purest form. The colours and so on in the petals are not something old—they are of this year.”9

If a plant is overnourished with excessive water, liquid manures, or other soluble fertilizers, this easily leads to an excess of “Moon forces.” In such a case, the leaf behaves too much like the earth below it. Agitated watery growth is stimulated by excessive fertilizers. Fungus and other “rust” diseases may migrate up into the leaves and stem away from their proper place in the soil below because the plant above ground is too soft and thereby provides a suitable substrate for pathogenic fungi, which, in a balanced soil, would mostly remain in the earth. If the plant is able to dry itself out properly, to become more “cosmic” in its aridity above ground, fungus would not find a suitable home. Many of our pests are cold-blooded — they require a blanket of warmth around them, and soft-bodied pests often require a blanket of moisture as well. If these conditions can be removed, many pests simply move to more hospitable plants. If overfertilizing is strong enough, this wateriness extends all the way up beyond the leaves into the flowers and seed — as in the case of “corn smut” where fungus grows in the over-saturated seeds that are unable to dry out properly.

In the garden, it is all we ever to balance wet and dry, cold and hot, earthly and cosmic. The more attentive we are to such processes, the more successful we are and the greater fertility we can nourish wherever we find ourselves growing.

Biodynamics in the Dry Tropics

The conditions of each piece of land and its interactions with the climate are infinitely varied combinations whose expression gives rise to the vegetation we observe growing in a given place. Plants contain active forces and processes that find material ready to take shape.

John Ruskin, Proserpina https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/20421/pg20421-images.html

G. Grohman, The Plant, vol. 2, pg 69.

R. Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture VIII (GA327, 16 June, 1924, Koberwitz)

See: Karl Koenig, Earth and Man

John Ruskin, Proserpina https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/20421/pg20421-images.html

John Ruskin, Proserpina https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/20421/pg20421-images.html

Alan Chadwick, Lecture by Alan Chadwick in New Market, Virginia, 1979, Lecture 8: Fertility, Part 2, http://www.alan-chadwick.org/html%20pages/lectures/virginia_lectures/chadwick-virginia-fertility-8-2.html

Charles Taylor, Cosmic Connections, pg. 75.

Rudolf Steiner, Physiology and Healing, pp. 85-86 CW314.